When Generations Collide Over Television’s Most Controversial Character

There are certain television shows that define entire generations, and “All in the Family” undoubtedly sits at the top of that list. Running from January 1971 through April 1979, with its continuation as “Archie Bunker’s Place” extending until April 1983, this Norman Lear masterpiece broke every rule in the television playbook. It brought racism, sexism, economic inequality, and political division into American living rooms with unflinching honesty wrapped in comedy. For those of us who watched it during its original run, we knew we were witnessing something revolutionary—a show that didn’t just entertain but challenged, provoked, and started necessary conversations that echoed around dinner tables across America.

But here’s the critical question that’s been burning in my mind: How does this groundbreaking series land with audiences who weren’t alive during its original broadcast? What happens when someone from a completely different generation and cultural perspective encounters Archie Bunker for the first time? To find out, I asked my colleague Ainsley Andrade, a young man of color who had never seen the show, to watch several episodes and share his unfiltered thoughts. What he revealed was both surprising and deeply illuminating about how dramatically our cultural lens has shifted.

The Great Generational Divide

For context, I’m old enough to have experienced “All in the Family” during its groundbreaking first run. Even as a young viewer, I recognized it as something extraordinary—a sitcom that dared to hold up a mirror to American society’s ugliest prejudices while somehow making people laugh. The genius of the show, as I understood it then and now, was that audiences laughed at Archie Bunker, not with him. His bigotry wasn’t celebrated; it was exposed as the product of ignorance, limited education, and generational prejudice passed down through a cycle of poverty and abuse.

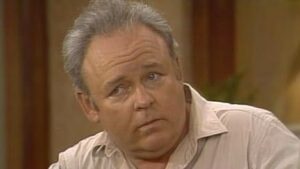

Carroll O’Connor’s portrayal of Archie was nothing short of masterful. He created a character who was simultaneously infuriating and oddly sympathetic—a working-class man struggling to keep his head above water while the world changed rapidly around him. Archie wasn’t a villain dripping with malice; he was a buffoon whose outdated views were constantly challenged and often proven ridiculous by his progressive son-in-law Mike, his budding feminist daughter Gloria, his open-hearted wife Edith, and his Black neighbor Lionel Jefferson. The show’s brilliance lay in presenting bigotry not as acceptable, but as ignorant and increasingly obsolete.

Norman Lear himself once noted in interviews that when he looks back on Archie Bunker, he sees a man who never had any fun—a tragic figure trapped by his own limitations and prejudices, unable to fully embrace the love and community available to him if he could just let go of his hatred.

A Modern Viewer’s Shocking Verdict

I expected Ainsley to appreciate the show’s historical significance and perhaps even find Archie’s linguistic butchery and constant humiliation amusing. Instead, his response was visceral and uncompromising. In his own words from his recent column: “Archie Bunker was a racist, sexist piece of sh*t with this heart of gold that everyone keeps talking about but that I’m too busy being offended by to find. I’ve programmed myself to shut people like that out and take solace in the idea that one day society will leave their ancient and bigoted ways behind, like the ignorant dinosaurs that they are.”

Oof. That stung, even though I understood where he was coming from. Ainsley, like many young people today, has zero tolerance for bigotry in any form, even when presented as comedy or social commentary. He’s been raised in an era where representation matters, where microaggressions are identified and called out, and where the idea of laughing at a racist character—even one designed to expose racism’s absurdity—feels deeply uncomfortable and potentially harmful.

Why Context Matters—And Why It Doesn’t

When I discuss “All in the Family” with younger viewers, I always try to provide historical context. In 1971, television offerings were extraordinarily limited. If you were lucky, you had three major networks producing content designed primarily to please advertisers, maybe a PBS channel, and a handful of local stations. Programming was safe, sanitized, and designed to offend absolutely nobody. Shows featured idealized families with perfect mothers like Jane Wyatt in “Father Knows Best,” Donna Reed in “The Donna Reed Show,” and Barbara Billingsley in “Leave It to Beaver.”

Into this vanilla landscape exploded “All in the Family,” featuring a working-class family struggling with real economic pressures, generational conflicts, and the massive social upheaval of the early 1970s. For the first time, a sitcom acknowledged that racism existed, that families argued about politics, that women were questioning their traditional roles, and that the American Dream wasn’t equally accessible to everyone. The show didn’t just break the fourth wall—it demolished it entirely.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth that Ainsley’s reaction illuminated: historical context doesn’t automatically make something palatable or acceptable to modern audiences. Just because something was revolutionary for its time doesn’t mean it translates seamlessly across generations. The cultural distance between 1971 and 2026 is vast, and what seemed like brave social commentary then can feel painfully outdated or even offensive now.

The Uncomfortable Question of Legacy

To his credit, Ainsley didn’t dismiss “All in the Family” entirely. Despite his initial revulsion, he recognized something crucial: “Maybe the reason that any of that stuff worked at all is because Carroll O’Connor gave us the villain that we needed him to be. If after 50 years of impacting American culture this show’s greatest achievement is the space it would eventually create for other works to push the envelope and address the issues they feel that they must, then I’d say that all of that would have been impossible without O’Connor being the ally we all needed by giving us the villain we all hope to one day live without.”

This perspective represents a fascinating reframing of the show’s legacy. Rather than celebrating Archie as a lovable curmudgeon whose heart eventually softened (which is how many of us remember him), Ainsley sees him as a necessary villain—a cultural lightning rod that had to exist so that better, more progressive content could eventually emerge. It’s a less romantic view of the show’s impact, but perhaps a more honest one from the perspective of someone who has access to decades of subsequent television that built upon what “All in the Family” started.

What We Lose When We Can’t See Past Offense

Yet I can’t help but feel that Ainsley’s understandable offense prevented him from seeing the full picture of what “All in the Family” accomplished. The show wasn’t just about Archie’s bigotry—it was about his growth, however slow and incomplete. Over the course of the original series and “Archie Bunker’s Place,” we watched Archie evolve. In one particularly powerful episode of the latter, he was so disgusted by a lodge brother’s racist comments that he physically confronted the man and quit the organization entirely. That moment represented over a decade of character development, showing that even the most entrenched prejudices can soften through consistent exposure to different perspectives and genuine relationships across racial lines.

The show also gave us Edith Bunker, brilliantly portrayed by Jean Stapleton—an “ordinary” sitcom wife who existed in a universe far removed from the perfect housewives of previous television eras. We got Sally Struthers as Gloria, whose feminist awakening played out in real-time, and Rob Reiner as Mike “Meathead” Stivic, whose progressive values constantly challenged Archie’s worldview. And crucially, we got the Jefferson family—funny, outspoken Black characters who weren’t sidekicks or stereotypes but fully realized people with their own prejudices, dreams, and eventual spinoff success.

The Attention Span Problem

Perhaps part of the disconnect between older and younger viewers comes down to patience. Archie’s growth happened gradually over more than ten years of television. That kind of long-form character development seems almost quaint in an era of binge-watching, instant gratification, and rapidly shifting cultural conversations. Modern audiences expect characters to learn their lessons within a single episode or season arc at most. The idea of watching someone slowly, painfully unlearn decades of ingrained prejudice across hundreds of episodes doesn’t fit our current entertainment consumption patterns.

A Surprising Reminder About Baby Boomers

Here’s something that often gets lost in contemporary discussions about “All in the Family”: Mike, Gloria, and Lionel—the characters who were vocal supporters of civil rights, gay rights, women’s reproductive rights, helping the homeless, equality and inclusion for all, and who openly opposed war, racism, sexism, homophobia, economic inequality, and environmental destruction—were Baby Boomers. The generation that’s now often criticized for being out of touch was once the progressive force pushing America toward greater justice and equality. “All in the Family” captured that generational battle in real time, showing how social progress happens through constant, exhausting dialogue between people who see the world differently.

The Verdict: You Had to Be There—But Should That Matter?

In the end, Ainsley’s assessment forced me to confront an uncomfortable reality: appreciating “All in the Family” as anything more than a historical artifact may require having experienced it in its original context. For those of us who were there, Archie Bunker represented exposure to perspectives and conversations that television had never dared to present before. For younger viewers like Ainsley, Archie is just another racist whose presence on screen feels unnecessary and uncomfortable, regardless of the show’s intentions or ultimate message.

Both perspectives are valid. The show was genuinely groundbreaking and opened doors for more diverse, honest storytelling on television. But that doesn’t mean everyone needs to find it enjoyable or even tolerable by today’s standards. Perhaps that’s the ultimate lesson “All in the Family” can teach us now—that progress means eventually outgrowing even our most revolutionary moments, and that’s not a failure but a success.