When All in the Family exploded onto television screens in 1971, America was burning—literally and figuratively. The Vietnam War raged overseas while cities from Washington, D.C., to Detroit still bore scars from riots following Martin Luther King’s assassination. Young people like me were abandoning urban centers, heading west in what we optimistically called the “back to the land” movement, searching for something more authentic than the sanitized families we’d grown up watching on Leave It to Beaver and Ozzie and Harriet.

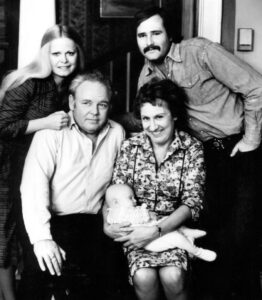

Archie Bunker stayed in Queens, stubbornly clinging to his belief that “a bar was a man’s castle,” while his daughter Gloria and son-in-law “Meathead” struggled to help him understand hippies, protests, and a rapidly transforming America. We chuckled with Meathead while our dads got their laughs from Archie. The show captured a generational divide that felt insurmountable at the time.

But here’s what neither Archie’s family nor those pristine 1950s sitcom families could have predicted: America was about to change in ways that would make those culture clashes seem quaint. My own family’s journey—occasionally dysfunctional, frequently challenging, ultimately beautiful—reflects what America is actually becoming. And I’d argue it’s closer to the reality most families are navigating today than anything television has ever shown us.

Building a Family Across Continents

My journey began far from the television families of my youth. In 1965, I joined the Peace Corps and spent most of the next five years in Turkey. I’d grown up in Minnesota and California, the child of immigrant families from Germany and Norway—already a blend of cultures, though it didn’t feel that way at the time. In Turkey, I met another Peace Corps volunteer from Pennsylvania whose family roots traced to Italy and Poland. We married and, in 1971, just as Archie Bunker was hitting the airwaves, we moved to rural northeast Oregon.

We arrived at a pivotal moment in adoption history. As the Vietnam War dragged on, adoption services began bringing mixed-race Vietnamese children to the United States, followed by poor children from India and Central America. This represented a seismic shift—American adoptions had only recently emerged from secrecy. Historically, they were hush-hush affairs with unmarried mothers quietly sent to “visit faraway aunts” while doctors discreetly arranged placements.

In 1976, we adopted a one-year-old white boy born in New Jersey and brought to Oregon by a mother too young and poor to raise him. Seven years later, in 1983, we adopted a boy from Calcutta, estimated to be six years old. We believed we had everything these children needed: love, stability, and the opportunity to enter the American mainstream. We were naive about what we didn’t understand.

The Trauma We Didn’t See Coming

What we failed to grasp was that children bring their past trauma with them, no matter how much love you pour into their present. We also never imagined how difficult being brown in eastern Oregon would become.

Our white son faced his next wave of trauma when a classmate committed suicide in his presence. The experience shattered him. He transferred schools, channeled his pain into becoming a star athlete, went to college—and struggled. Eventually, he joined the Navy and married a woman whose father served in Vietnam and whose mother is from the Philippines. Their road appears smooth now, but getting there required navigating trauma we hadn’t anticipated and couldn’t fully understand.

For our brown son, color wasn’t initially an issue. When the kids were young, rural Oregon seemed welcoming enough. But as he hit junior high, conscious and unconscious racial slurs grew louder and more frequent. He heard the N-word more than once. He transferred schools twice. At eighteen, he moved to Portland without graduating from high school. He had children but couldn’t manage them, circumstances that led to me raising a mixed-race grandson and granddaughter in eastern Oregon—beginning the cycle again.

History Repeating: Raising the Next Generation

The early years with my grandchildren were easy, just as they had been with their father. But history repeated itself with painful precision. Racial slurs murmured in school hallways and on athletic fields made their high school years extraordinarily difficult. “How’s being black?” a classmate wrote casually in my grandson’s yearbook—a question that reveals so much ignorance disguised as innocent curiosity. His friendships withered. He channeled his anger onto the football field, using football as an outlet for pain he couldn’t express elsewhere. His sister graduated online and moved away as quickly as she could.

I didn’t fully comprehend how isolated they both felt until my grandson enrolled at nearby Eastern Oregon University. There, the student body is twenty-five percent non-white—a dramatic contrast to his high school experience. He loves college. For the first time in his life, he’s not constantly marked as different, not perpetually othered. He can simply exist.

An Unexpected Christmas That Changed Everything

Their father, born in Calcutta and raised in Oregon, eventually found his path and his partner in Phoenix, Arizona. She’s an immigrant too, from Uganda, and together they built a family. One Christmas, they came to visit with their two-year-old son. The apprehension on all sides was palpable. If brown gets noticed in small-town northeast Oregon, what would locals do with this new Indian-African family?

The two-year-old stole everyone’s hearts—at home and in town. Something shifted during that visit. The grandchildren I raised began understanding their father’s difficult journey as they embarked on their own adult paths in a rapidly changing America. Empathy replaced resentment. Context replaced confusion.

The America We’re Becoming

Even eastern Oregon is growing multi-colored now. Mexican and Thai restaurants have opened. Students arrive from across the world. American Indian communities are experiencing resurgence and reclaiming space. The transformation is neither complete nor easy, but it’s undeniable.

My grandchildren—brown and Black, representing the heritage of four continents and one island nation—are gaining confidence. They’re building lives that would have been unimaginable to my German-Norwegian-American grandparents, to my parents, and certainly to Archie Bunker. They will grow my family tree in directions that defy every expectation of what an American family should look like.

The journey hasn’t been easy. We made mistakes rooted in naivety and privilege. We believed love alone could overcome systemic racism and generational trauma. We learned painfully that it cannot—but it’s still essential. Love combined with awareness, education, advocacy, and the willingness to listen when our children tell us about pain we cannot fully understand—that’s what’s required.

This is what America is becoming: messy, complicated, beautiful, and impossibly diverse. Families that span continents and cultures. Children who navigate multiple identities. Communities slowly, sometimes grudgingly, expanding their definitions of belonging.

It won’t be easy. Progress never is. But looking at my grandchildren, at their resilience and their growing confidence, at the family we’ve built across so many borders and boundaries—I believe it’s not just inevitable. It’s a genuinely good thing.

Archie Bunker couldn’t have imagined this America. But here we are, living it, building it, one complicated, beautiful family at a time.