From Rejection to Television Immortality: The Untold Story of How Rob Reiner Became Meathead

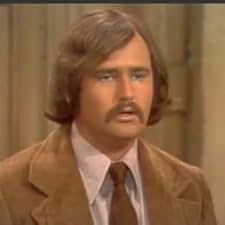

Imagine “All in the Family” without Rob Reiner. Impossible, right? The character of Michael “Meathead” Stivic is so intrinsically linked to Reiner’s performance that separating the two feels like trying to imagine “The Godfather” without Marlon Brando. Yet television history came dangerously close to taking that exact turn. Rob Reiner was rejected not once, but twice before finally landing the role that would define his acting career and help revolutionize American television comedy.

The story of how Reiner almost lost his shot at immortality reveals the chaotic, unpredictable nature of television production in the early 1970s, and demonstrates how sometimes failure becomes the unexpected pathway to success.

The Role That Required Walking a Tightrope

Understanding why Norman Lear initially passed on Reiner requires understanding just how complex and demanding the role of Mike Stivic truly was. On paper, Mike seemed straightforward enough: the progressive college student son-in-law who served as the ideological counterweight to Archie Bunker’s reactionary conservatism. Mike represented the Baby Boomer counterculture—long-haired, college-educated, anti-war, and determined to drag America kicking and screaming into a more enlightened future.

But Lear’s genius lay in refusing to make Mike simply a heroic liberal mouthpiece. Instead, Mike embodied the contradictions and hypocrisies that plagued even well-intentioned progressives. He was the educated white guy who lectured about social justice while remaining blind to his own ingrained prejudices, particularly regarding women. He was the activist more interested in winning arguments and feeling morally superior than actually doing the hard work of creating change. He was insufferably self-righteous, often condescending, and frequently as closed-minded as the father-in-law he constantly battled.

Playing this walking contradiction required an actor capable of making Mike simultaneously sympathetic and infuriating, right and wrong, heroic and hypocritical—often within the same scene. When Reiner first auditioned, apparently he hadn’t yet developed the maturity and nuance that such a demanding role required.

The First Rejection: ABC’s Lost Opportunity

“All in the Family” didn’t spring fully formed onto CBS in 1971. The show’s journey to the screen was as tumultuous as the arguments between Archie and Mike. Norman Lear had originally developed the concept for ABC, which commissioned not one but two pilot episodes. Reiner auditioned during this early ABC phase and was rejected. The network executives, famous for their conservative approach to programming, were already nervous about the show’s controversial content. They ultimately passed on the series entirely, a decision that would go down as one of the biggest missed opportunities in television history.

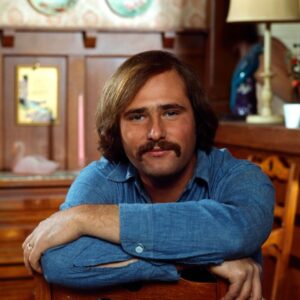

During this period, Reiner found himself cast as a writer on “Headmaster,” Aaron Ruben’s short-lived dramedy starring Andy Griffith. The show represented Griffith’s attempt to shed his folksy “Andy Griffith Show” persona by playing the headmaster of a prestigious California private school dealing with serious contemporary issues. The series lasted only thirteen episodes before cancellation, but one particular episode would inadvertently change Reiner’s career trajectory forever.

The Scandalous Role That Changed Everything

In the third episode of “Headmaster,” titled “Valerie Has an Emotional Gestalt for the Teacher,” Reiner wasn’t just writing—he was acting. He played a young teacher caught having an affair with a student, one of those volatile storylines that “Headmaster” attempted to tackle with the dramatic seriousness that “All in the Family” would later address with uncomfortable comedy.

The episode is virtually impossible to find and watch today, lost to the vault of forgotten television history. We can only speculate how the show handled such explosive subject matter. But what we know is this: Reiner’s performance as a male authority figure engaged in deeply inappropriate behavior, likely still convinced of his own righteousness despite his misconduct, caught Norman Lear’s attention.

There was something in Reiner’s portrayal—perhaps the way he captured moral blindness, or how he embodied the gap between self-perception and reality—that made Lear reconsider his earlier rejection. Reiner had demonstrated exactly the kind of complex, layered performance that Mike Stivic would demand.

The Second Chance: CBS Takes a Gamble

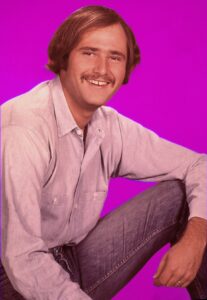

When CBS picked up “All in the Family” after ABC’s rejection, Norman Lear had the opportunity to produce a third pilot. Some roles were already locked in: Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton had proven irreplaceable as Archie and Edith Bunker from the beginning. Their chemistry and performances were so perfect that reimagining anyone else in those roles was unthinkable.

But Gloria and Mike had been recast for each pilot. Sally Struthers and Rob Reiner became the third couple to play the Bunker children, and they would be the ones who finally made it to series. As Reiner recalled in an interview with the Archive of American Television, his path back to auditioning was directly connected to his “Headmaster” performance:

“That episode was one of the reasons I got ‘All in the Family.’ I believe I had auditioned when it was a pilot at ABC. ‘All in the Family’ had done two pilots at ABC and then, when it eventually got on, it got on at CBS. And Sally Struthers and I were the third set of Mike and Gloria. And I remember auditioning for an earlier version, they said I didn’t get it. But I think Norman Lear saw my work in that episode and I auditioned again. He felt I had matured as an actor, I think, and gave me the part on the CBS version.”

The Maturity Factor: What Changed Between Auditions

Reiner’s self-assessment about his own maturation as an actor is revealing. The role of Mike Stivic required more than just the ability to deliver progressive talking points or engage in heated political debates. It required an actor who could reveal layers of complexity, who could make audiences simultaneously root for Mike’s ideals while cringing at his self-righteousness, who could embody both the promise and the pitfalls of a generation determined to change the world.

Whatever growth Reiner experienced between his first and second auditions—whether from life experience, additional acting work, or simply time—was enough to convince Norman Lear that this time, he had found his Meathead.

The Chemistry That Made Television History

Once cast, Reiner and Struthers developed the kind of natural chemistry that cannot be manufactured or forced. Their portrayal of Mike and Gloria felt authentic, capturing both the passion of young marriage and the tensions that arise when two people are still figuring out who they are while living under someone else’s roof. The cramped quarters of the Bunker household, with Mike and Gloria occupying the upstairs bedroom, created perfect conditions for multi-generational conflict.

Reiner’s performance evolved throughout the show’s nine-season run, as Mike matured from idealistic student to struggling provider to eventually finding his own path separate from the Bunker household. The character’s journey mirrored the disillusionment many Baby Boomers experienced as the optimism of the 1960s counterculture gave way to the harder realities of the 1970s.

The Legacy of Almost Not Happening

Reiner would go on to win two Emmy Awards for his portrayal of Mike Stivic and use his “All in the Family” fame as a launching pad for one of the most successful directing careers in Hollywood history, helming classics like “The Princess Bride,” “When Harry Met Sally,” “A Few Good Men,” and “Stand By Me.” But none of that happens if Norman Lear doesn’t give him a second chance, if that obscure “Headmaster” episode doesn’t demonstrate Reiner’s growth as an actor, if CBS doesn’t pick up the show after ABC’s rejection.

The story serves as a reminder that rejection isn’t always final, that timing matters as much as talent, and that sometimes the roles we’re meant to play only become available after we’ve grown into the people capable of playing them. Rob Reiner almost wasn’t Meathead. Television almost missed one of its most iconic performances. And “All in the Family” almost looked very, very different.

Thank goodness Norman Lear believed in second chances.