The phone call that would change television history came down to six words. CBS executives had made their position crystal clear: remove “11:30 on a Sunday morning?” from the premiere episode of “All in the Family,” or there would be consequences. Norman Lear faced a choice that would define not just his career but the future of American television—surrender creative control over something seemingly trivial, or risk everything by drawing a line in the sand before his revolutionary show even reached audiences.

His response became legendary: “If you don’t play that line, I won’t be in tomorrow.” This wasn’t negotiation or artistic temperament—it was recognition that if he backed down on this battle, he’d lose the war before it began. But what made these six ordinary words so dangerous that network executives were willing to kill the most talked-about new show in development? The answer reveals everything about what Norman Lear was really fighting for, and why his gamble would earn him the personal enmity of President Richard Nixon himself.

The Revolution Nobody Wanted

Norman Lear knew exactly what firestorm he was igniting with “All in the Family.” Industry veterans, network executives, and nervous advertisers had warned him repeatedly that Americans—particularly the white, straight, conservative Americans who dominated cultural conversations in 1971—would revolt against a sitcom that tackled hot political topics without apology, that refused to sugarcoat the country’s racist history, that showed how religion could be weaponized to justify bigotry against “the other.” These weren’t paranoid fears. They were based on decades of understanding what American television audiences supposedly wanted and could tolerate.

The skeptics had valid reasons for their concerns. Despite being adapted from the British series “Till Death Us Do Part,” nothing remotely resembling “All in the Family” existed on U.S. airwaves. American sitcom fathers were paragons of wisdom and tolerance—Andy Taylor gently guiding Mayberry toward righteousness, Ward Cleaver dispensing patient wisdom, even widower Steve Douglas maintaining good humor through any crisis. These men didn’t scream ethnic slurs at their sons-in-law. They didn’t justify prejudices through twisted logic. They certainly didn’t exist in homes where you could hear toilets flush or witness adult children being caught in compromising positions.

“All in the Family” was designed to demolish every single one of these comfortable television fictions. Archie Bunker—played brilliantly by Carroll O’Connor—wasn’t a father who knew best. He was a working-class bigot whose prejudices weren’t charming quirks but genuine character flaws with real consequences. He called his son-in-law “Meathead,” hurled epithets with casual cruelty, and twisted religious teachings to justify hatreds he wouldn’t examine. This was television daring to show how families actually behaved when the door closed—messy, argumentative, loving despite fundamental disagreements, and thoroughly, authentically human.

The Scene That Started Everything

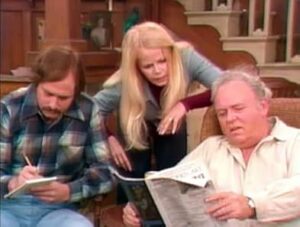

The premiere episode, “Meet the Bunkers,” announced its revolutionary intentions from the opening moments. Archie and his wife Edith—the long-suffering but unexpectedly wise Jean Stapleton—return home from church earlier than expected. What they discover sends shockwaves through the established order of television propriety: their daughter Gloria (Sally Struthers) and her husband Mike (Rob Reiner), whom Archie contemptuously calls “the Meathead,” are engaged in marital intimacy. Not suggested through knowing glances, not alluded to via clever innuendo, but actually interrupted mid-act.

The scene itself should have been the controversy. Previous sitcoms treated married sexuality like state secrets, acknowledged only through the most careful euphemisms. Yet remarkably, CBS didn’t object to showing the interrupted couple. What terrified network executives was something far more subtle: Archie’s response. His very first line, delivered with characteristic outrage: “11:30 on a Sunday morning?”

Norman Lear recounted the ensuing battle to the New York Post in 2021, and his description reveals exactly what CBS feared: “The network wanted that line out. Why? Because he’s talking about 11:30 on a Sunday morning and it implants a picture in the audience’s mind.”

Why Six Words Became the Battle for Television’s Soul

CBS’s objection seems absurd at first glance. The scene already showed what was happening—why would mentioning the time make it worse? But network executives understood something that made those six words genuinely dangerous: Archie’s emphasis on “11:30 on a Sunday morning” forced audiences to actively imagine what they’d just witnessed. The time reference was specific, relatable. The Sunday morning detail added scandalous context—this wasn’t just sex, it was sex mere hours before church time, possibly even after church for the young couple.

Most insidiously, from CBS’s perspective, Archie’s incredulous repetition made viewers complicit. They couldn’t passively watch—they had to mentally reconstruct the scene from Archie’s scandalized viewpoint, putting themselves in his position, imagining their own children or being caught themselves. That active participation, that “implanting a picture in the audience’s mind” as CBS delicately phrased it, was precisely what television had spent decades carefully avoiding.

Lear recognized this moment for what it truly represented: a test of whether he could make the show he envisioned or whether he’d suffer death by a thousand cuts, each seemingly small censorship demand adding up to complete creative emasculation. “I remember thinking, if the line comes out, I’m going to be in trouble from then on with the silliest things,” he recalled. “So that was our first disagreement. I said, ‘If you don’t play that line, I won’t be in tomorrow.'”

This wasn’t bluster. Lear understood that if CBS could remove a simple time reference because it made audiences think too explicitly about what they’d seen, then nothing would be safe. Every honest moment, every uncomfortable truth, every reflection of how families actually lived would be subject to network interference based on what pictures it might “implant” in viewers’ minds. The show would become another sanitized lie about American life—exactly what Lear was fighting against.

The Time Zone That Saved Television

The standoff created genuine uncertainty about whether “All in the Family” would air as Lear intended. Then geography provided an unexpected resolution. Because of the three-hour time difference between coasts, the show aired in New York before CBS executives in California could watch the final cut and potentially intervene. “It wasn’t until the show went on the air in New York, three hours earlier [than California] and someone from my family called and said that it was [kept] in,” Lear remembered with obvious satisfaction.

By the time California executives saw the episode, millions of New Yorkers had already heard “11:30 on a Sunday morning?” The sky hadn’t fallen. Viewers hadn’t rioted. The line had simply worked, creating exactly the effect Lear intended—making audiences confront the reality that married couples have sex at unexpected times, that families catch each other in embarrassing situations, that life is messier than television had previously admitted.

The Revolution That Followed

That first victory proved prophetic. “All in the Family” didn’t just ruffle feathers—it plucked them systematically throughout its groundbreaking run. The show tackled subjects that previous sitcoms wouldn’t touch: sexual assault received serious, unflinching treatment; menopause was discussed openly rather than whispered about; infidelity, homophobia, racism, sexism, religious hypocrisy—every uncomfortable aspect of American life became fair game.

The show didn’t just reference current events peripherally—it dove into them. The Vietnam War wasn’t background noise but the subject of bitter family arguments. Watergate wasn’t just news but a topic that divided the Bunker household. Civil rights, women’s liberation, every major social upheaval of the 1970s played out through personal conflicts between family members who loved each other despite fundamental disagreements about how the world worked.

Most remarkably, these weren’t abstract political debates. Archie’s bigotry clashed with Mike’s liberal idealism through intensely personal arguments about specific situations. Edith’s simple faith provided unexpected moral clarity when everyone else got lost in rhetoric. Gloria navigated between her father’s traditional expectations and her own evolving feminism. These were real families having real arguments that millions of Americans recognized from their own dinner tables.

When the President Declared War on a Sitcom

Perhaps no validation of “All in the Family’s” cultural impact came clearer than earning Richard Nixon’s personal ire. The president—himself a frequent subject of discussion on the series and never in flattering terms—viewed the show as emblematic of everything wrong with modern television. That the most powerful man in America felt threatened by a sitcom about a working-class family in Queens demonstrated how effectively “All in the Family” had penetrated the national consciousness and challenged comfortable assumptions.

Yet through all the controversy, all the hand-wringing from critics who insisted the show would destroy American values, audiences responded with overwhelming enthusiasm. “All in the Family” didn’t just survive—it dominated, becoming the number one show in America for five consecutive years. Viewers didn’t tune in despite the controversial content; they tuned in because of it.

The show’s live studio audience reactions revealed this hunger for authenticity. Yes, they laughed at Archie’s malapropisms and the clever exchanges between characters. But they also responded with explosive emotion to dramatic moments—gasping at revelations, falling silent during serious discussions, erupting in applause when characters stood up for what was right. These weren’t just comedy fans; they were people who recognized their own lives, their own families, their own arguments in what they saw on screen.

The Line That Changed Everything

Looking back, that ultimatum over six words represented far more than a dispute about television standards. It was the moment American television chose truth over comfortable lies. It was the moment a creator chose artistic integrity over network compliance. It was the moment audiences were finally trusted to handle honest reflections of their own lives.

Norman Lear’s gamble on “11:30 on a Sunday morning?” wasn’t really about sex or censorship—it was about whether television would continue infantilizing audiences or start treating them like adults capable of recognizing and grappling with complexity. His willingness to walk away over something seemingly trivial communicated to CBS that he meant business, that “All in the Family” would tell the truth or not exist at all.

Lear, as it turned out, was right after all. Americans didn’t need television to lie to them about who they were. They didn’t need sanitized versions of family life that bore no resemblance to their own experiences. They needed television brave enough to show them the truth—that families fight, that parents can be wrong, that love coexists with disagreement, and that confronting our prejudices and hypocrisies is the first step toward becoming better.

That single act of defiance over six words changed television forever, opening the door for every honest, complicated, challenging show that followed. All because Norman Lear understood that sometimes the most revolutionary act is simply telling the truth, and that the truth is worth risking everything for—even if the battle comes down to something as seemingly small as mentioning the time on a Sunday morning.