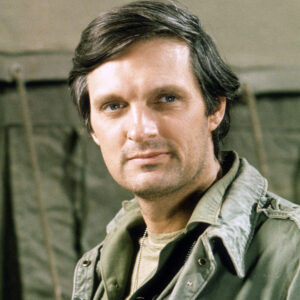

Hawkeye Pierce wasn’t just the heart and soul of MAS*H—he was one of television’s most complex, controversial, and captivating characters ever created. Portrayed brilliantly by Alan Alda across eleven seasons and 251 episodes, Captain Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce became the lens through which millions of viewers experienced the Korean War. But behind the wisecracks and martinis lies a character far more intricate than most fans realize.

The Name That Almost Wasn’t

Benjamin Franklin Pierce earned his nickname “Hawkeye” from his father, who was a fan of James Fenimore Cooper’s “The Last of the Mohicans.” This literary connection wasn’t just a throwaway detail—it revealed something fundamental about Hawkeye’s character. Like his fictional namesake, Hawkeye Pierce was a skilled observer, a survivor in hostile territory, and someone who bridged different worlds. His father, Daniel Pierce, was a country doctor in Crabapple Cove, Maine, and young Benjamin grew up watching his dad treat everyone regardless of their ability to pay. This upbringing shaped Hawkeye’s fierce egalitarianism and his belief that medicine should serve humanity, not bureaucracy or military hierarchy.

Interestingly, Alan Alda initially hesitated to take the role. He was concerned about playing a character originated by Donald Sutherland in Robert Altman’s 1970 film. Alda worried he couldn’t match Sutherland’s anarchic energy and feared being compared unfavorably. However, producer Gene Reynolds convinced him that television would allow for a deeper, more nuanced exploration of the character over time—and history proved Reynolds spectacularly right.

A Surgeon Who Hated War

What made Hawkeye revolutionary for television was his unwavering anti-war stance despite being a military officer. He wasn’t a conscientious objector or a deserter—he was a draftee who fulfilled his duty while never hiding his contempt for the war itself. This complexity made him fascinating. Hawkeye would work thirty-six-hour shifts saving lives, then spend his downtime drinking, joking, and subverting military authority at every opportunity.

His surgical skills were portrayed with remarkable authenticity. The show employed real medical consultants, and Alda learned actual surgical techniques to make the operating room scenes believable. Hawkeye’s hands-on competence contrasted sharply with his irreverent attitude, showing that excellence and rebellion could coexist. He could perform a delicate arterial repair while cracking jokes, then break down crying when a young soldier died on his table. This emotional range made him feel achingly real.

The character’s anti-war philosophy evolved throughout the series. Early Hawkeye was more of a prankster who used humor to cope. Later seasons showed a man increasingly traumatized by the endless stream of casualties, someone whose jokes became darker and whose drinking became heavier. By the series finale, Hawkeye suffered a complete psychological breakdown, repressing a traumatic memory that finally surfaced during therapy. This arc showed that war doesn’t just kill—it wounds the survivors in ways that never fully heal.

The Ladies’ Man with Depth

Hawkeye’s reputation as a womanizer was legendary within the 4077th, but his relationships with women were far more complicated than simple conquest. Yes, he dated nurses, flirted constantly, and seemed to have a new romance every few episodes. However, the show gradually revealed that Hawkeye’s serial dating was another coping mechanism—a way to feel alive and human in the midst of death and destruction.

His most significant relationship was arguably with Major Margaret Houlihan. What began as mutual antagonism evolved into deep respect and genuine friendship. Their relationship showed Hawkeye’s capacity for growth. He went from objectifying “Hot Lips” to recognizing Margaret as a skilled professional and complex person. Some of the series’ most touching moments came from their conversations, particularly after Margaret’s divorce when Hawkeye provided comfort without trying to seduce her.

The episode “Comrades in Arms” revealed another layer to Hawkeye’s romantic life. Trapped behind enemy lines with Margaret, they became intimate, but the experience was portrayed with unusual sensitivity for 1970s television. It wasn’t about conquest—it was about two people seeking comfort and connection when facing possible death. When they returned to camp, both recognized that what happened couldn’t continue, showing mature emotional intelligence rarely seen in TV characters of that era.

The Friendship That Defined Him

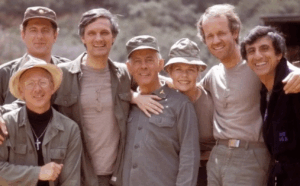

Hawkeye’s friendships were the emotional core of MAS*H, none more important than his relationships with his tentmates. His bond with Trapper John McIntyre in the early seasons showed two kindred spirits united in their hatred of war and love of mischief. When Trapper left without saying goodbye, Hawkeye’s devastation was palpable, revealing how much he depended on these connections to maintain his sanity.

B.J. Hunnicutt’s arrival in season four created television’s most enduring male friendship. Unlike Trapper, B.J. was faithful to his wife and more emotionally grounded, serving as Hawkeye’s conscience and anchor. Their relationship deepened over seven seasons, surviving arguments, jealousies, and the strain of war. The series finale’s emotional climax came when B.J., who had always refused to say goodbye, left Hawkeye a message spelled out in stones: “GOODBYE.” It was a perfect encapsulation of their bond—B.J. knew Hawkeye needed that closure even if it hurt to give it.

Hawkeye’s friendship with Radar O’Reilly showed his protective, almost paternal side. He looked out for the naive farm boy from Iowa, teaching him about life while learning innocence and hope from Radar in return. When Radar left to care for his mother, Hawkeye’s reaction showed how much he valued these surrogate family relationships.

The Martini-Swilling Philosopher

Hawkeye’s drinking was a constant throughout the series, but it was never played purely for laughs. His homemade gin, brewed in the Swamp, was both a running gag and a symbol of his need to self-medicate. The show acknowledged that Hawkeye used alcohol to numb himself to the horrors he witnessed daily. In later seasons, episodes directly addressed his alcohol consumption, showing it as a problem rather than just a quirky character trait.

His philosophical musings, often delivered while drunk or exhausted, revealed a deeply thoughtful man grappling with impossible moral questions. How do you reconcile saving lives with being part of a war machine? How do you maintain humanity when surrounded by inhumanity? Hawkeye never found satisfying answers, and the show respected viewers enough not to provide easy resolutions. His struggles with these questions made him relatable—we all face moral ambiguities, even if not in such extreme circumstances.

The Prankster with Purpose

Hawkeye’s legendary pranks on Frank Burns and later Charles Winchester weren’t just for entertainment—they were acts of resistance against military pomposity and rigid hierarchy. When he and Trapper painted Major Burns’s toes while he slept or when he convinced Winchester that his expensive French horn was cursed, Hawkeye was asserting that human dignity and humor mattered more than rank and protocol.

His most elaborate prank involved convincing the entire camp that he was dying, complete with fake symptoms and a dramatic farewell. The joke backfired when he realized how much everyone genuinely cared about him, leading to a rare moment of Hawkeye feeling guilty about a prank. This episode showed that even his humor had limits and consequences.

The Doctor Who Broke Barriers

Alan Alda’s portrayal of Hawkeye broke television conventions in numerous ways. He insisted on showing the realities of war without sanitizing them. Operating room scenes showed blood, exhaustion, and the desperate fight to save lives. Hawkeye’s emotional breakdowns were raw and uncomfortable, not melodramatic. Alda fought to eliminate the laugh track from these scenes, arguing that death wasn’t funny even in a comedy.

Hawkeye also challenged traditional masculinity for television. He cried openly, admitted fear and vulnerability, and expressed deep love for his male friends without embarrassment. In an era when male characters were expected to be stoic and unemotional, Hawkeye’s emotional honesty was revolutionary. He showed that strength included acknowledging weakness, that courage meant admitting fear.

The Legacy of a Flawed Hero

What makes Hawkeye Pierce endure as a character is that he was never perfect. He could be self-righteous, obnoxious, and insensitive. His constant joking sometimes hurt people. His drinking was problematic. His treatment of women, while progressive for the era, wouldn’t pass muster by modern standards. But these flaws made him human and relatable.

The series finale, “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen,” gave Hawkeye’s character arc a devastating conclusion. His breakdown and recovery showed that even the strongest people have breaking points, and that seeking help is strength, not weakness. When he finally boarded the helicopter to leave Korea, Hawkeye was fundamentally changed—scarred but surviving, traumatized but still capable of connection and hope.

Hawkeye Pierce remains relevant because his struggles are timeless. How do we maintain our humanity in inhumane circumstances? How do we cope with trauma and loss? How do we find meaning in senseless situations? These questions resonate just as powerfully today as they did in the 1970s and 1980s.

Through 251 episodes, Hawkeye evolved from a wise-cracking surgeon into one of television’s most fully realized characters—a flawed, funny, brilliant, broken man who showed us that surviving isn’t the same as being unscathed, and that laughter and tears are often the same response to an absurd and tragic world.