There are moments in entertainment history when you can pinpoint the exact second everything changed. January 12, 1971, was one of those nights. As American families gathered around their television sets for what they thought would be just another sitcom, they had no idea they were about to witness a revolution. “All in the Family” was about to premiere, and absolutely nobody—not the network executives, not the cast, not even creator Norman Lear himself—was certain whether they’d created a masterpiece or committed career suicide on national television.

Third time’s the charm, they say, and for Norman Lear’s groundbreaking sitcom, that old adage proved prophetically true. After two failed pilot attempts that left CBS executives deeply skeptical, “All in the Family” finally hit the airwaves with an episode fittingly titled “Meet the Bunkers.” What unfolded in those revolutionary twenty-four minutes was unlike anything American television had ever dared to broadcast into living rooms across the nation.

A Deceptively Simple Beginning

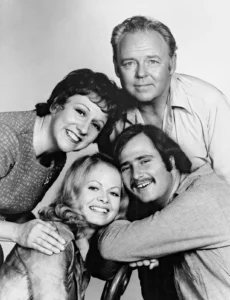

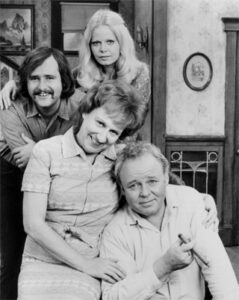

The premiere episode was, on its surface, remarkably simple. There was barely a plot to speak of. Archie Bunker, brilliantly portrayed by Carroll O’Connor, did what he would do for the next nine seasons: he argued, pontificated, and revealed his bigotry with every breath. His son-in-law Michael, better known as Mike and played by Rob Reiner, squabbled with him over religion and politics like it was their personal competitive sport. Archie’s daughter Gloria, brought to life by Sally Struthers, oscillated between irritation and tears as she desperately tried to maintain peace between the stubborn men dominating her life. And through it all, Archie was deservedly and hilariously made to look like a clown for his prejudices, only for the episode to wrap up with unexpected earnestness that explained why his loved ones tolerated him at all.

Like any television pilot, the characters weren’t fully formed yet. Sharp-eyed viewers watching that first episode would notice significant differences from what the show would become. Archie’s wife Edith, portrayed by the incomparable Jean Stapleton, was considerably sassier than her later incarnation. She cracked jokes about their honeymoon night and openly mocked Archie when he dramatically overreacted after gripping the wrong end of a coffee pot. Meanwhile, Mike and Gloria could barely keep their hands off each other even within Archie’s direct line of sight, their youthful passion on full display in a way that would cause significant behind-the-scenes controversy.

Walking on Eggshells Into History

But beneath the surface of that first episode, there was something else—a palpable sense of trepidation, of cautious steps into uncharted territory. The show’s cast and crew knew they were going where no American sitcom had ventured before. Despite being adapted from the largely identical British hit “Till Death Us Do Part,” which had successfully navigated similar controversial waters across the Atlantic, there remained a suffocating fog of doubt hanging over the production. American television in 1971 was a different beast entirely, with different sensibilities and different limits. Would American viewers embrace this bold new approach to comedy, or would they riot? Would advertisers flee? Would the network pull the plug before the pilot even finished airing?

The Network’s Panic: A Disclaimer That Screamed Uncertainty

To characterize CBS as nervous would be the understatement of the decade. The network executives were so terrified of potential backlash that they took the unprecedented step of running a lengthy disclaimer before the show even started. Viewers were warned that “All in the Family” “seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show — in a mature fashion — just how absurd they are.”

Rob Reiner, in a brutally honest 2016 interview with American Masters, cut through the corporate-speak to reveal what that disclaimer really meant: “We don’t have anything to do with this show.” CBS was essentially creating plausible deniability, establishing distance between themselves and this controversial experiment just in case everything went horribly wrong. It was a lengthy, anxiety-drenched way of telling the American public that if they were offended, they shouldn’t blame the network.

“We Thought It Was Our Swan Song”

The fear wasn’t confined to network boardrooms. The cast and crew themselves were convinced they’d just participated in television history’s most spectacular failure. Sally Struthers, in a revealing interview with The Dispatch decades later, painted a picture of a group of artists certain they’d be unemployed by morning.

“When we first went on, we thought we were going to be taken off the air,” Struthers admitted with remarkable candor. “We knew the show was going to infuriate some people, and make some people reel in disgust. Once the first [episode] aired we thought it was going to be our swan song. Little did we know that within a year we’d be number one.”

The cast believed they were, as Struthers put it in echoing Reiner’s sentiment, “too hip for the room.” They’d created something too bold, too honest, too raw for mainstream American audiences to accept. As they watched that first episode air, knowing it was being beamed into millions of homes across the country, they genuinely believed they were witnessing both the beginning and the end of their grand experiment.

The Twist Nobody Saw Coming

But then something extraordinary happened. Instead of the predicted outrage and cancellation, “All in the Family” sparked conversation. America didn’t recoil in horror—they leaned in with fascination. The show that everyone thought was career suicide became the most-watched program in the nation within a year. It would run for nine glorious seasons, spawn multiple spinoffs including “Maude,” “The Jeffersons,” and “Good Times,” and continue with a direct sequel series, “Archie Bunker’s Place.”

Most importantly, “All in the Family” fundamentally changed what American sitcoms could be. Comedy series had tackled thorny subjects before the Bunkers arrived—even “Bewitched” had aired an episode denouncing racism—but those shows had cloaked their messages in fantasy and metaphor. Norman Lear’s creation gave television permission to speak plainly, to abandon playful conceits, and to address real issues with real language that real Americans actually used in their own homes.

Why It Mattered Then and Still Matters Now

Starting with “Meet the Bunkers,” the audience’s own “frailties, prejudices, and concerns” were laid bare for the world to see and examine. Characters could be flawed, complicated, and even bigoted without being villainized beyond recognition. Archie Bunker was lovable despite his prejudices, not because the show excused them, but because it showed him as fully human—capable of love, vulnerable to fear, and occasionally, just occasionally, capable of growth.

The show proved that Americans were far more sophisticated than network executives had given them credit for. They could handle nuance. They could laugh at uncomfortable truths. They could see themselves in these characters and, through that recognition, perhaps reflect on their own biases and blind spots.

There was no going back after “All in the Family” premiered. Television comedy had been fundamentally altered, expanded, and elevated. And thank goodness for that. What began with a terrified cast, panic-stricken executives, and a defensive disclaimer became one of television’s greatest success stories—proof that sometimes taking the biggest risks yields the most extraordinary rewards.

The cast thought they’d filmed their swan song. Instead, they’d created a legend.