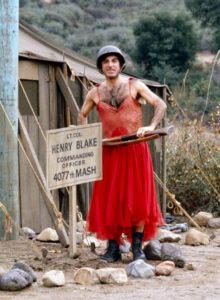

Maxwell Q. Klinger, the Toledo native who wore dresses to get a Section 8 discharge, began as a one-episode gag character and evolved into one of MASH’s most complex, beloved, and surprisingly profound figures. Jamie Farr’s portrayal transformed what could have been a cheap running joke into a multifaceted character who embodied resilience, loyalty, and the universal desire for home while challenging assumptions about masculinity, sanity, and what it means to survive impossible circumstances with dignity intact. Klinger’s journey from comic relief to emotional anchor demonstrates MASH’s genius for finding humanity in unexpected places and respecting characters enough to let them grow beyond their initial premises.

His Schemes Were Actually Brilliant Acts of Resistance

Klinger’s elaborate attempts to secure a psychiatric discharge through cross-dressing and increasingly outrageous behavior appeared comedic on the surface, but represented something far more significant—creative resistance against a system that trapped individuals in circumstances beyond their control. Unlike characters who expressed anti-war sentiment through philosophical arguments or cynical commentary, Klinger enacted physical, visible protest every single day by refusing to conform to military masculine norms. His dresses, wigs, and accessories weren’t just costumes for laughs; they were acts of defiance that challenged military authority’s ability to define acceptable manhood.

What made Klinger’s resistance particularly clever was its operating within a loophole—military regulations stated that mentally unfit soldiers should be discharged, so he performed mental unfitness in ways that were simultaneously hilarious and strategically sound. The military couldn’t punish him for wearing dresses without acknowledging that such behavior indicated genuine psychiatric issues requiring discharge. His schemes grew progressively more elaborate and creative, from attempting to eat a Jeep to staging his own wedding to a non-existent woman, each new attempt demonstrating remarkable ingenuity and commitment to his goal.

The deeper brilliance lay in how Klinger’s resistance maintained his humanity and individuality in an environment designed to strip both away. Military service demands conformity, obedience, and suppression of personal identity in favor of collective mission. By insisting on his own unique, outrageous presentation, Klinger refused erasure. His schemes became artistic expressions of selfhood, performances that said “I am still Maxwell Klinger from Toledo, Ohio, and you cannot make me forget that.” This theme of maintaining identity against dehumanizing forces resonated powerfully with audiences, particularly during an era when many questioned military service’s personal costs. Klinger’s desperate creativity in pursuing his goal made him not just funny but genuinely heroic—a man who never stopped fighting to reclaim his own life.

Beneath the Comedy Was Profound Vulnerability and Pain

As MAS*H evolved from broader comedy toward darker dramedy, Klinger’s character revealed layers of genuine pain and psychological struggle beneath his outrageous exterior. The show increasingly acknowledged that his schemes weren’t just silly antics but manifestations of real desperation from someone traumatized by war and circumstances beyond his control. Episodes exploring Klinger’s emotional state showed a man barely holding himself together, using humor and spectacle as coping mechanisms against overwhelming fear and homesickness.

Particularly powerful were moments when Klinger’s façade cracked to reveal raw vulnerability. Scenes where he spoke about Toledo with longing that bordered on physical pain, or when he broke down crying while describing what he was missing at home, transformed him from comic character to tragic figure. His homesickness wasn’t played for laughs but portrayed as genuine suffering—the pain of someone torn from everything familiar and meaningful, forced into a nightmare with no clear end date. The show demonstrated that Klinger’s constant scheming to go home wasn’t laziness or cowardice but a reasonable response to unbearable circumstances.

Jamie Farr’s performance brilliantly navigated the tonal complexity required, able to generate laughs one moment and break hearts the next without the shifts feeling jarring. He brought such sincerity to Klinger’s pain that even while wearing absurd outfits, the character’s suffering felt authentic and deeply moving. The vulnerability Farr portrayed challenged audience assumptions about both the character and masculinity itself—showing that a man in a dress expressing profound emotional need was worthy of respect and empathy rather than mockery. This revolutionary representation demonstrated that strength doesn’t require emotional suppression, that wearing women’s clothing doesn’t diminish a man’s humanity, and that the desire to go home isn’t weakness but natural human longing.

He Was Fiercely Loyal and Deeply Principled

One of Klinger’s most admirable qualities, and one that became more prominent as the series progressed, was his unwavering loyalty to his friends and his strong moral code. Despite his constant schemes to escape military service, when his friends needed him, Klinger showed up completely and selflessly. He risked his own safety numerous times to protect others, volunteered for dangerous assignments to spare colleagues, and provided emotional support to fellow personnel struggling with their own demons. His loyalty wasn’t conditional or performative—it was bone-deep integrity that defined who he was.

This created fascinating character complexity—Klinger desperately wanted to leave but would never abandon people who depended on him. He hated military service but loved the individuals serving alongside him. This contradiction made him profoundly human and relatable. Most people understand the experience of being trapped in situations we hate while still caring deeply about the people sharing that trap with us. Klinger embodied this universal tension between personal desires and communal responsibilities, and consistently chose loyalty over self-interest even when it cost him dearly.

His moral code extended beyond personal relationships to encompass broader principles of justice and compassion. Klinger consistently stood against prejudice, defended the vulnerable, and spoke truth to power regardless of consequences. When he witnessed injustice toward Korean civilians, racism within the camp, or abuse of authority, he intervened even when staying silent would have been safer. His principles weren’t abstract philosophy but lived values demonstrated through action. This moral backbone, combined with his outrageous presentation, created a character who challenged assumptions about who deserves respect and whose values matter. Klinger proved that integrity and courage exist independent of conventional presentation, that a man in a dress holding a purse could embody heroic principles as effectively as any traditionally masculine soldier.

His Cultural Pride Was Revolutionary Representation

Klinger’s proud Lebanese-American identity and his constant references to Toledo’s Lebanese community provided rare and important representation during an era when television rarely acknowledged ethnic diversity within American identity. He spoke Arabic phrases, referenced Lebanese customs and food, and expressed fierce pride in his heritage without ever being reduced to stereotype. This representation mattered enormously to Arab-American viewers who rarely saw themselves reflected in mainstream media, and it educated broader audiences about the diversity within American society.

What made this representation particularly significant was that Klinger’s ethnicity wasn’t his defining characteristic or the butt of jokes. He was a fully realized character who happened to be Lebanese-American, and his cultural background enriched rather than limited his characterization. His love of Toledo and his Lebanese community there demonstrated how ethnic identity and American identity coexisted naturally, that being proudly Lebanese and proudly American weren’t contradictory but complementary. This nuanced portrayal countered prevailing narratives that demanded ethnic minorities assimilate and abandon cultural heritage to be authentically American.

Jamie Farr, himself of Lebanese descent and from Toledo, brought authenticity to these elements that made Klinger’s cultural identity feel genuine rather than tokenistic. The references to Lebanese food, family traditions, and community weren’t written as exotic otherness but as normal elements of American life, because for millions of Americans, they were. This normalization of Arab-American identity was quietly revolutionary, creating space for viewers to see ethnic diversity as fundamental to rather than separate from American identity.

His Character Growth Was Earned and Beautifully Realized

Klinger’s evolution from desperate schemer to responsible leader represented some of MAS*H’s finest character development. The transformation wasn’t sudden or convenient but gradual and organic, built through accumulated experiences that changed him without erasing who he fundamentally was. As the war dragged on and Klinger realized it might outlast his schemes, he began investing more energy in his actual duties and discovered competence and even satisfaction in his work. He remained himself—still outrageous, still vocal about wanting to go home—but matured into someone who could balance personal desires with professional responsibilities.

The pinnacle of this growth came when Klinger eventually received his long-sought discharge and chose to stay in Korea to help with post-war reconstruction and to be with the Korean woman he loved. This decision, which could have felt like betrayal of his character’s defining goal, instead felt like the perfect culmination of his journey. Klinger had spent years desperate to leave, but he’d also spent those years building deep connections with people and place. His choice to stay wasn’t abandoning his dream but recognizing that he’d changed, that home wasn’t just geography but also the people and purposes that gave life meaning.

This conclusion honored both who Klinger had been and who he’d become. He got his discharge—the goal that defined him for years—but had grown into someone for whom that goal no longer represented his highest value. The man who stayed in Korea was still Maxwell Klinger, still the guy from Toledo who wore dresses and schemed outrageous plans, but also someone who’d discovered capacities for love, leadership, and service he hadn’t known he possessed. This character arc demonstrated MAS*H’s profound respect for its characters, allowing them to grow in ways that felt surprising yet inevitable, transformative yet authentic.

Klinger’s journey from one-note gag to complex, beloved character exemplifies everything MAS*H did brilliantly—finding humanity in unexpected places, respecting characters enough to let them evolve, using comedy to explore serious themes, and creating representation that expanded rather than limited our understanding of human diversity and dignity.