When Television Stopped Lying: The Revolutionary Truth of ‘All in the Family’

Television in the 1960s was a beautiful lie. Families never fought about anything serious. Parents dispensed wisdom with gentle smiles. Problems were solved in twenty-two minutes, commercials included. Shows like “Leave It to Beaver,” “Father Knows Best,” and “The Donna Reed Show” presented an America that existed only in the fantasies of network executives—sanitized, homogenized, and utterly divorced from the turbulent reality of American life.

Then, on January 12, 1971, everything changed. “All in the Family” premiered on CBS, and television would never be the same. This wasn’t just another sitcom debuting in a crowded landscape of forgettable entertainment. This was a cultural earthquake that shattered every convention about what television comedy could be, what it could say, and who it could challenge.

The Anti-Family That Felt Like Real Family

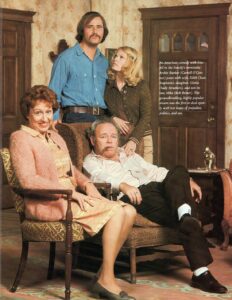

The Bunker household looked nothing like the pristine living rooms of television past. Their Queens, New York home was cramped, worn, and cluttered with the accumulated debris of working-class life. The furniture was dated, the décor was garish, and the atmosphere crackled with tension that could explode at any moment.

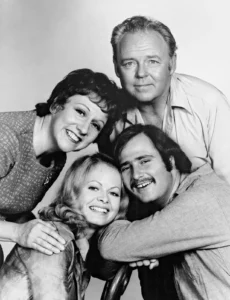

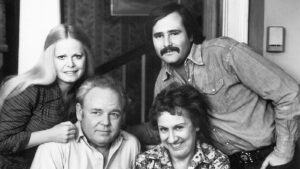

At the center sat Archie Bunker, portrayed with devastating complexity by Carroll O’Connor. Archie was a loading dock foreman whose worldview had calcified somewhere around 1955 and refused to budge despite the social upheavals reshaping America. He was loud, bigoted, xenophobic, homophobic, and sexist—a walking catalog of prejudices that polite society whispered about but never acknowledged on television.

Yet here’s the brilliant paradox that made “All in the Family” work: Archie was also somehow lovable. Not lovable in spite of his flaws, but lovable in a way that forced viewers to confront an uncomfortable truth—bigots aren’t cartoon monsters living in distant places. They’re our fathers, our uncles, our neighbors. They love their families, work hard, and genuinely believe they’re good people, even as they spout views that make progressive audiences recoil.

Carroll O’Connor’s genius lay in never winking at the audience, never signaling that Archie was just a character to be mocked. He played Archie with complete sincerity, as a man who believed every word he said, which made the character’s ignorance all the more devastating and all the more real.

The Bunker Household as America’s Battlefield

The true brilliance of “All in the Family” emerged in its family dynamics, which served as a microcosm for America’s cultural civil war. Archie’s wife Edith, played with heartbreaking warmth by Jean Stapleton, seemed at first glance to be the stereotypical submissive housewife—the “dingbat” that Archie constantly dismissed. But Edith possessed a moral clarity and emotional intelligence that often cut through the ideological warfare swirling around her. Her simple observations frequently revealed truths that both Archie’s conservatism and Mike’s progressivism missed.

Living upstairs were Gloria (Sally Struthers) and Mike “Meathead” Stivic (Rob Reiner), representing the Baby Boomer generation determined to drag America kicking and screaming into a more enlightened future. Mike was everything Archie despised—college-educated, long-haired, anti-war, and convinced of his own moral superiority. The battles between Archie and Mike weren’t just father-in-law versus son-in-law arguments. They were generational warfare, political combat, and philosophical showdowns rolled into explosive confrontations that left nothing off-limits.

But creator Norman Lear was too sophisticated to make Mike simply the heroic voice of reason. Mike had his own blind spots, his own hypocrisies, particularly regarding women and his inflated sense of self-righteousness. He was often more interested in winning arguments than creating actual change, more focused on feeling superior than understanding his opponents. This complexity prevented “All in the Family” from becoming simple propaganda, transforming it instead into nuanced social commentary.

Breaking Every Taboo: The Topics Other Shows Wouldn’t Touch

What truly separated “All in the Family” from every sitcom before it was its fearless approach to subjects that television had treated as radioactive. Racism wasn’t subtly implied—it was front and center, with Archie casually dropping slurs and expressing prejudices that made audiences gasp. The show confronted anti-Semitism, homophobia, women’s liberation, rape, miscarriage, menopause, impotence, the Vietnam War, Watergate, gun control, and economic inequality.

Episode after episode tackled issues that news programs discussed with grave seriousness, but “All in the Family” used comedy as its weapon. The show understood something revolutionary: humor could be a Trojan horse for social commentary. By making audiences laugh, the show disarmed their defenses, allowing difficult conversations to penetrate minds that might have remained closed to traditional messaging.

Consider how the show addressed racism through Archie’s character. Rather than creating a villainous racist for audiences to safely despise, the show presented Archie’s bigotry as casual, almost reflexive—the product of ignorance rather than malice. This approach was more unsettling because it was more accurate. Most prejudice doesn’t announce itself with white hoods and burning crosses. It lives in assumptions, jokes, and comfortable ignorance that decent people convince themselves is harmless.

By exposing Archie’s views to scrutiny and ridicule through Mike’s counterarguments and the consequences of Archie’s prejudices, the show invited viewers to examine their own biases. Some audiences rooted for Archie, some for Mike, but everyone was forced to engage with ideas that made them uncomfortable.

The Power of Authentic Dialogue

“All in the Family” pioneered a new kind of television writing that prioritized authentic conversation over joke-punchline formulas. Episodes featured extended arguments between characters, real discussions that meandered, escalated, and sometimes ended without resolution—just like actual family disagreements.

This commitment to realistic dialogue created an intimacy between the show and its audience. Watching the Bunkers argue felt like eavesdropping on your own family’s dinner table debates. The show didn’t lecture or preach. It presented multiple viewpoints, allowed characters to articulate their positions passionately, and trusted audiences to think critically about what they were witnessing.

The show also wasn’t afraid to break traditional sitcom structure. Some episodes ended on unresolved notes. Characters sometimes faced consequences that lasted multiple episodes or entire seasons. The show acknowledged that real social issues don’t get wrapped up neatly before the closing credits.

Cultural Impact That Transcended Entertainment

The impact of “All in the Family” extended far beyond television ratings, though it dominated those as well, becoming the number-one show in America for five consecutive years. The show fundamentally changed the national conversation about race, gender, politics, and social justice.

Topics that had been confined to academic discussions, activist circles, or whispered private conversations suddenly became dinner table debates. Families across America gathered to watch the Bunkers, then argued about the same issues the characters had just explored. The show didn’t just reflect cultural divisions—it provided a framework for discussing them.

Norman Lear had created something unprecedented: a sitcom that functioned as a national town hall, where Americans of all political persuasions tuned in and grappled with the same difficult questions. In an era before cable news fragmentation and social media echo chambers, “All in the Family” was one of the last cultural touchstones that united Americans in shared viewing, even as it highlighted their divisions.

The Controversial Legacy

Not everyone celebrated “All in the Family.” Critics argued that presenting Archie’s bigotry, even critically, risked normalizing it. Some viewers missed the satirical point entirely, embracing Archie as a hero standing up to political correctness before that term existed. The show received complaints from conservative groups who found it too liberal and from progressive organizations who worried it made prejudice too entertaining.

But perhaps this controversy was proof of the show’s power. Entertainment that makes everyone comfortable changes nothing. “All in the Family” made viewers squirm, argue, question their assumptions, and confront uncomfortable truths about themselves and their society. That discomfort was precisely the point.

Why It Still Matters Today

More than five decades after its premiere, “All in the Family” remains startlingly relevant. The issues that divided the Bunker household—racial justice, women’s rights, economic inequality, political polarization, generational warfare—still dominate American discourse. Turn on cable news or scroll through social media, and you’ll find Archie and Mike still arguing, just wearing different faces.

The show’s legacy lives on in every comedy that dares to tackle serious subjects, from “The Simpsons” to “South Park” to “Black-ish.” Norman Lear proved that television could entertain and enlighten simultaneously, that audiences were hungry for content that reflected their real lives rather than fantasy versions of them.

In our current era of polarization and fragmentation, “All in the Family” reminds us of a time when a single show could bring an entire nation together—not by avoiding controversy, but by diving headfirst into it with courage, humor, and the belief that understanding might follow laughter.

The Bunker family’s living room remains open, the arguments continue, and the lessons remain as urgent as ever.