The Living Room That Held America’s Heart One More Time

On January 15, 2024, the Peacock Theater in Los Angeles transformed into something far more intimate than a typical awards show venue. As the 75th Emmy Awards unfolded, two familiar faces stepped onto a set that instantly transported millions of viewers back to 704 Hauser Street in Queens—the fictional address that became as recognizable to Americans as their own homes. Rob Reiner and Sally Struthers, television’s beloved couple Michael and Gloria Bunker, reunited on a meticulously recreated version of the Bunker family living room to honor the man who had brought them together five decades earlier.

Norman Lear, the revolutionary television producer who transformed American sitcoms from escapist entertainment into vehicles for social commentary, had passed away on December 5, 2023, at the remarkable age of 101. He died peacefully at his Los Angeles home, surrounded by family, concluding a life that spanned over a century and reshaped the cultural landscape of television forever. The Emmys tribute wasn’t just about honoring a television legend—it was about celebrating a man who fundamentally changed what television could be, what it could say, and how deeply it could matter.

A Family Reunion Decades in the Making

When Rob Reiner stepped forward to begin the tribute, his words carried the weight of both personal loss and professional gratitude. “Sally and I were part of a unique television family,” he began, his voice steady but emotional. “Not just the Bunkers, but Norman Lear’s extended family.” That single sentence encapsulated something profound about Lear’s approach to television production—he didn’t just hire actors and crew members, he created families, both on screen and off.

Reiner continued, choosing his words carefully: “Norman brought us together and created shows that depicted real people who made us laugh, made us think, made us feel.” In that simple statement lay the entire philosophy that distinguished Lear’s work from virtually everything else on television in the early 1970s. Before Norman Lear, sitcoms were safe, predictable, and carefully designed to offend absolutely no one. After Norman Lear, television could be dangerous, provocative, and designed to start conversations that made people uncomfortable—and that was precisely the point.

Sally Struthers, standing beside her television husband on that recreated set, added her own perspective on the evening’s larger meaning. “Tonight, as we remember the legends of our industry we lost this past year, we celebrate their lives and legacy,” she said, her words honoring not just Lear but the entire community of television pioneers who had passed during that difficult year.

The Refrain That Defined an Era

Then came the moment that sent chills through viewers watching at home and brought tears to eyes in the theater. Together, Reiner and Struthers delivered the line that had opened every episode of “All in the Family,” the nostalgic refrain that became synonymous with the show itself: “Those were the days.” It was more than just a callback to the show’s iconic theme song—it was an acknowledgment that something extraordinary had existed, something that changed television forever, and that the architect of that revolution had now passed.

The choice of those specific words carried multiple layers of meaning. On one level, it referenced the show’s opening theme, which Archie and Edith sang together, looking back with rose-colored glasses at a simpler time that probably never actually existed. On another level, it acknowledged that the era of Norman Lear’s dominance of television—when he had multiple shows in the top ten simultaneously, when his vision of what sitcoms could be reshaped the entire medium—truly were special days that would never come again.

The Revolution That Started in a Living Room

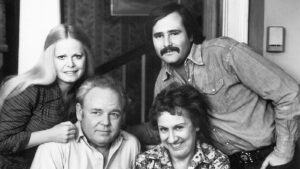

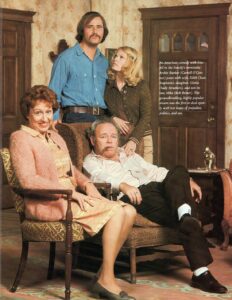

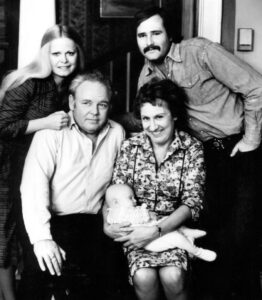

Understanding why this tribute mattered requires understanding what Norman Lear accomplished with “All in the Family.” The show, which originally premiered on CBS in 1971, was based on the British sitcom “Till Death Us Do Part,” but Lear transformed it into something uniquely American and revolutionary. He centered the show around Archie Bunker, played by Carroll O’Connor, a working-class loading dock foreman whose bigoted views collided weekly with his liberal son-in-law Michael “Meathead” Stivic, played by Reiner.

But Lear did something unprecedented: he made Archie simultaneously the show’s antagonist and its heart. Viewers could laugh at Archie’s ridiculous prejudices while also understanding his economic anxieties, his fear of a changing world, and his genuine love for his family. This complexity—this refusal to make any character entirely hero or villain—elevated “All in the Family” beyond typical sitcom fare into something approaching art.

The show fearlessly tackled subjects that had been considered untouchable in television comedy. Abortion. The Vietnam War. Racial prejudice. Sexual assault. Women’s liberation. Homosexuality. Menopause. Archie’s ignorance became the vehicle for exploring America’s most divisive issues, and somehow, impossibly, the show managed to address these topics with both humor and humanity.

A Legacy Measured in Impact, Not Just Awards

“All in the Family” ran for nine groundbreaking seasons and won three Emmy Awards for Outstanding Comedy Series, but those statistics barely scratch the surface of its cultural impact. The show dominated the Nielsen ratings, becoming the number one show in America for five consecutive years—a feat matched by few shows before or since. More importantly, it changed what was possible in television.

The success of “All in the Family” led to an unprecedented string of spin-offs that extended Lear’s vision across multiple shows and demographics. “Maude” brought feminist issues to primetime. “The Jeffersons” became the first sitcom to depict an affluent African American family living in Manhattan. “Good Times” showed a working-class Black family navigating poverty and systemic racism. “Archie Bunker’s Place” continued exploring Archie’s character evolution after Edith’s death. Each show maintained Lear’s commitment to addressing real issues through the lens of humor and humanity.

“Am I Not the Luckiest Dude?”

In the statement released by Lear’s family after his death, they shared something that perfectly captured his perspective on his extraordinary life. Throughout his later years, Lear would often reflect on his career, his family, and his longevity by asking, “‘Am I not the luckiest dude?'” That sense of gratitude, that awareness of how extraordinary his journey had been, characterized Lear’s approach to life right up until the end.

And perhaps that was the final lesson Norman Lear taught through his work and his life: that you could tackle difficult subjects, challenge your audience, push boundaries, and provoke thought while still maintaining a sense of joy, gratitude, and fundamental humanity. He lived 101 years, created or developed over one hundred television shows, won six Emmy Awards, received the National Medal of Arts, and was inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame. But beyond all those accomplishments, he proved that television could be more than just entertainment—it could be a catalyst for social change, a mirror held up to society, and a vehicle for conversations America desperately needed to have.

The Days That Still Matter

When Rob Reiner and Sally Struthers said “Those were the days” on that Emmy stage, they weren’t just being nostalgic. They were reminding us that there was a time when television had the courage to challenge viewers, when sitcoms could make you laugh and think in equal measure, when one producer’s vision could reshape an entire medium. Norman Lear created those days, and in doing so, he ensured they would never be forgotten.

The Bunker living room set may have been temporary, erected just for that one tribute moment, but what it represented—and what Norman Lear built—remains permanent in television history.