For eleven seasons, MASH transported millions of viewers to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in Korea, creating one of television’s most authentic and immersive worlds. What audiences didn’t realize was the extraordinary behind-the-scenes effort, innovation, and occasional chaos that made this illusion possible. The production of MASH involved creative problem-solving, obsessive attention to detail, and production techniques that were revolutionary for 1970s television. These five fascinating facts about how MAS*H was actually made reveal that the real story behind the cameras was almost as dramatic as the fiction unfolding in front of them.

The Entire Series Was Filmed at a California Ranch

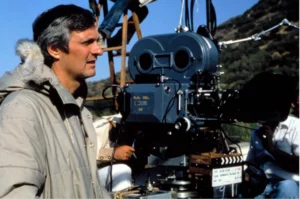

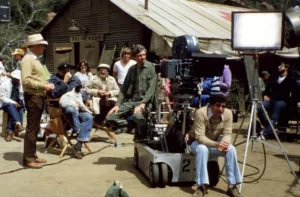

One of MASH’s most impressive achievements was creating a convincing Korean War setting without ever leaving California. The exterior scenes—the iconic 4077th compound with its distinctive tents, helicopter pad, and surrounding hills—were filmed at the Malibu Creek State Park ranch in the Santa Monica Mountains, about 25 miles from Hollywood. This location became so synonymous with MASH that it’s now a tourist destination where fans can visit the actual filming site.

What makes this location choice fascinating is how the production team transformed a Southern California landscape into convincing Korea. The vegetation was wrong, the climate was different, and the terrain didn’t naturally match Korea’s geography. Production designers worked meticulously to modify the environment, importing specific plants, carefully controlling which angles were filmed to avoid obviously Californian vistas, and using the natural rock formations and hills to create authentic-looking backgrounds.

The ranch location created interesting production challenges and advantages. On one hand, having a permanent outdoor set allowed for consistency across episodes and seasons—viewers became intimately familiar with the 4077th’s layout because it actually existed as a physical space rather than being recreated for each filming. The crew could leave the set standing between shoots, which saved time and money while increasing authenticity.

However, the California location also meant dealing with weather that didn’t match Korea’s climate. The production frequently had to work around Southern California’s drought conditions, bright sunshine, and lack of seasonal variety. When episodes required rain, snow, or specific weather conditions, production had to create these effects artificially. The famous opening sequence helicopter shot, which remained consistent throughout the series’ eleven-year run, was filmed once and reused in every episode—a practical decision that became an iconic piece of television history.

Interior scenes were filmed on soundstages at the 20th Century Fox studios, where the production built incredibly detailed recreations of the surgical tent, Swamp (where Hawkeye and his roommates lived), mess tent, and other interior locations. These sets were built with such authenticity that real military medical equipment was used, and the level of detail extended to areas never visible on camera. This obsessive attention to environmental detail helped actors inhabit their characters more fully and contributed to the show’s authentic atmosphere.

A Real Army Surgeon Served as Full-Time Medical Consultant

MAS*H’s medical authenticity wasn’t accidental—it resulted from having actual military medical personnel serving as consultants throughout the production. Most notably, Dr. Walter Dishell, a surgeon who had served in Korea, worked closely with the show as a medical advisor. His involvement went far beyond simply reviewing scripts; he was present on set during filming, teaching actors proper surgical technique, ensuring medical procedures looked authentic, and catching errors that would have undermined the show’s credibility.

Dr. Dishell’s influence permeated every aspect of MAS*H’s medical scenes. The actors didn’t just pretend to perform surgery—they learned actual surgical techniques and proper handling of medical instruments. Alan Alda became particularly proficient, studying surgical procedures so intensively that Dr. Dishell reportedly said Alda could have assisted in actual surgeries. This dedication to authentic performance meant that when viewers watched operating room scenes, they were seeing actors perform realistic approximations of actual medical procedures rather than theatrical gestures.

The medical equipment used on set was real, often borrowed from or donated by medical supply companies and hospitals. The surgical tent set contained authentic operating tables, anesthesia equipment, surgical instruments, and monitoring devices. This authenticity created a working environment that felt genuine to the actors, helping them deliver more convincing performances. It also meant the show could be used as an educational tool—medical schools occasionally showed MAS*H episodes to demonstrate triage principles, combat surgery challenges, and medical ethics under pressure.

Dr. Dishell’s consulting extended to storylines and character development. Writers would consult him about realistic medical scenarios, asking what kinds of injuries would arrive from specific combat situations, what treatments would be available with 1950s technology in field conditions, and what emotional and psychological challenges surgeons would face. This input helped MAS*H avoid the medical impossibilities that plagued other television shows, lending the series credibility that enhanced its dramatic impact.

The show’s medical authenticity occasionally created interesting challenges. Some procedures or injuries that would have been realistic were deemed too graphic for television audiences. Dr. Dishell had to help the production team find the balance between medical accuracy and viewer comfort, suggesting how to film procedures that conveyed the reality of combat surgery without becoming unwatchably disturbing. This delicate calibration allowed MAS*H to be honest about war’s physical costs without traumatizing viewers.

The Cast Frequently Rewrote Scripts and Improvised Dialogue

Unlike many television productions where scripts were treated as sacred text, MAS*H encouraged significant actor input into dialogue and character development. Alan Alda became increasingly involved in writing and directing episodes, eventually penning 19 episodes and directing 32. But even when not officially credited as writers, cast members frequently revised their own dialogue, improvised in scenes, and suggested character developments that writers incorporated.

This collaborative creative process resulted from the show’s evolution from traditional sitcom to something more sophisticated. Early seasons followed typical television production hierarchies, with writers creating scripts and actors performing them as written. But as the cast developed deeper understanding of their characters and the show’s creative team recognized the value of actor insight, the production became more collaborative. Actors who had lived with their characters for years understood nuances that writers might miss, and their suggestions often improved scenes significantly.

Alan Alda was particularly influential in shaping Hawkeye’s character development. He pushed for storylines that explored Hawkeye’s psychological struggles, his growing trauma, and the moral complexities of being a healer in a war zone. Many of Hawkeye’s most powerful moments—particularly in later seasons—reflected Alda’s creative vision and writing as much as the credited screenwriters. His involvement helped ensure Hawkeye evolved beyond the wisecracking surgeon of early seasons into the psychologically complex, deeply wounded character of later years.

Loretta Swit fought tirelessly for Margaret’s dignity and development, suggesting storylines and revising dialogue that she felt reduced her character to a one-dimensional stereotype. Her insistence that Margaret be portrayed as a competent, complex professional rather than just “Hot Lips” gradually transformed the character. Writers learned to consult Swit about Margaret’s choices and reactions, recognizing that she understood her character’s psychology and motivation better than anyone.

The show’s willingness to incorporate improvisation also created some of its most memorable moments. Actors occasionally ad-libbed lines that were so perfect they made it into final cuts. The loose, conversational feel of many scenes—particularly those in the Swamp or mess tent—resulted partly from allowing actors to find natural rhythms and responses rather than adhering rigidly to scripted dialogue. This approach required tremendous trust between directors, writers, and actors, but it resulted in performances that felt spontaneous and authentic rather than overly rehearsed.

Production Shut Down Multiple Times Due to Cast Conflicts and Creative Disputes

While MAS*H is remembered for its excellence, the production wasn’t always harmonious. Several times during the show’s eleven-year run, filming halted due to conflicts between cast members, disputes over creative direction, or contract negotiations. These behind-the-scenes tensions occasionally threatened the show’s continuation and revealed that creating great art often involves navigating difficult interpersonal dynamics and conflicting visions.

Gary Burghoff, who played Radar, had increasingly difficult relationships with some cast members and struggled with the pressures of television production. His decision to leave after Season 7 resulted partly from on-set tensions and his desire to escape the demanding production schedule. The show handled his departure carefully, creating a gradual exit for Radar that honored the character while acknowledging the actor’s need to move on.

Wayne Rogers’ departure after Season 3 resulted partly from creative frustrations and feeling that Trapper John was being overshadowed by Hawkeye. Rogers wanted more substantial storylines and felt the show had become too focused on Alan Alda’s character. His dissatisfaction led to his decision not to renew his contract, forcing the production to write out Trapper and introduce BJ Hunnicutt. This cast change could have destroyed the show but instead opened new creative possibilities.

McLean Stevenson’s exit involved similar dynamics. His desire to pursue other opportunities and be a leading man rather than an ensemble player led to Henry Blake’s shocking death. These departures revealed tensions between actors’ career ambitions and long-running series’ demands. Not every actor wanted to commit to the same character for potentially a decade or more, regardless of the show’s success.

Even among cast members who remained throughout the run, there were occasional conflicts about creative direction, screen time, and character development. These were professionals with strong opinions about their characters and the show’s evolution. Sometimes those opinions clashed, requiring producers to mediate disputes and find compromises that kept the production functional.

The Production Team Used Innovative Techniques That Changed Television

MAS*H pioneered numerous production techniques that were revolutionary for 1970s television and influenced countless shows that followed. The decision to sometimes film without a laugh track, though controversial, changed how comedies could be produced. The show’s gradual evolution toward single-camera production without studio audiences reflected cinematic ambitions unusual for television sitcoms.

The production employed innovative cinematography that elevated television’s visual language. Directors used longer takes, allowing scenes to play out without constant cutting. They employed handheld cameras to create documentary-style realism in episodes like “The Interview.” The show experimented with point-of-view shots, surreal dream sequences, and visual storytelling techniques typically associated with prestige cinema rather than weekly television.

Sound design on MAS*H was also innovative. The production used ambient sound—distant helicopters, camp noise, surgical equipment—to create immersive soundscapes that enhanced realism. The famous helicopter sound that became synonymous with the show wasn’t just background noise; it was carefully integrated to create constant reminder of war’s presence and the endless cycle of wounded arrivals.

The show’s editing evolved to support more complex storytelling. Rather than adhering to strict sitcom timing with predictable beats for laugh track insertion, later seasons employed more sophisticated pacing that served dramatic needs rather than comedy formulas. This evolution demonstrated television’s potential for sophisticated narrative construction.

The Legacy of Innovation

These five fascinating production facts reveal that MASH’s excellence resulted from extraordinary effort, creative innovation, and willingness to challenge television conventions. The show’s creators, cast, and crew didn’t just make television—they reimagined what television could be. Their dedication to authenticity, willingness to experiment, collaborative creative process, and technical innovation transformed MASH from a sitcom into art. Understanding how the show was actually made deepens appreciation for its achievement and reminds us that great art requires not just talent but tremendous dedication, courage, and innovation behind the scenes.