In most television shows, villains are straightforward—evil for the sake of being evil, obstacles to overcome, or caricatures designed to be despised. But MASH operated on a different level entirely. The series understood that the most compelling antagonists aren’t mustache-twirling bad guys but complex characters whose opposing viewpoints challenge our heroes in meaningful ways. The real genius of MASH was recognizing that sometimes the antagonist isn’t a person at all, but a system, an ideology, or the circumstances that force impossible choices. Let’s examine four perfect antagonists that elevated MAS*H from a good show to a masterpiece of television storytelling.

Major Frank Burns: The Antagonist You Love to Hate

Frank Burns, portrayed brilliantly by Larry Linville, was MAS*H’s most visible human antagonist for the first five seasons. On the surface, he seemed like a simple comic foil—incompetent, hypocritical, cowardly, and self-righteous. He was the butt of endless pranks by Hawkeye and Trapper John, a pompous surgeon whose medical skills were questionable at best, and a man who preached morality while carrying on an affair with Major Margaret Houlihan.

But what made Frank Burns a perfect antagonist wasn’t his buffoonery; it was how he represented everything the show critiqued about blind institutional loyalty and unexamined privilege. Frank believed in military hierarchy not because it made sense, but because it placed him above others. He wrapped himself in patriotism and religion while demonstrating neither true love of country nor Christian compassion. His character forced viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about how institutions protect incompetent people who follow rules without understanding their purpose.

Larry Linville later revealed that playing Frank Burns was exhausting because the character had no redeeming qualities, yet this was precisely what made him effective. Frank never learned, never grew, and never self-reflected. He was a mirror held up to the worst aspects of authoritarian thinking, showing audiences exactly what happens when people value conformity over competence and appearance over authenticity. When Frank finally left the series after a mental breakdown, it felt both inevitable and tragic—a man so committed to a false self that reality ultimately shattered him.

Major Charles Emerson Winchester III: The Worthy Adversary

When David Ogden Stiers joined MAS*H as Charles Winchester in season six, the show evolved its approach to antagonism. Unlike Frank Burns, Charles was an exceptional surgeon, genuinely cultured, and intellectually formidable. He could match wits with Hawkeye, out-perform BJ in the operating room, and command respect through competence rather than rank.

Charles Winchester represented a more sophisticated form of antagonism—the worthy opponent who challenges heroes to be better. His Boston Brahmin background and elitist attitudes clashed with the 4077th’s informal egalitarianism, but Charles wasn’t wrong about everything. His insistence on proper surgical technique saved lives. His classical music provided genuine solace in chaos. His private acts of charity, like anonymously sending money to his sister’s speech therapy, revealed depth beneath the aristocratic facade.

What made Charles perfect as an antagonist was that he forced both characters and viewers to examine their own prejudices. It’s easy to dismiss someone as a snob, but Charles demonstrated that class consciousness and genuine excellence can coexist with hidden vulnerability. Episodes like “Death Takes a Holiday” and “Run for the Money” showed a man struggling with his own limitations and the gap between his privileged upbringing and the brutal equality of war. Charles Winchester proved that the best antagonists make protagonists question themselves, not just oppose them.

Military Bureaucracy: The Invisible Enemy

The most consistent antagonist in MAS*H wasn’t any individual character but the military bureaucracy itself—the faceless system that sent contradictory orders, demanded impossible paperwork, and treated human beings as statistics. This institutional antagonist appeared in countless episodes: supply requisitions denied while unnecessary items arrived, promotions awarded to incompetents, talented personnel transferred at critical moments, and regulations that prioritized appearance over function.

Colonel Potter, despite being a career military man, spent much of his time fighting this bureaucratic monster. Episodes featuring officious inspectors, supply sergeants protecting their fiefdoms, and staff officers issuing absurd directives illustrated how institutions develop their own logic divorced from their original purpose. The military was supposed to win wars and support soldiers, yet the 4077th constantly battled their own side for basic supplies and autonomy to save lives.

This antagonist was perfect because it was realistic and timeless. Anyone who has worked in a large organization recognizes the frustration of rules that contradict their purpose, supervisors who’ve never done your job making critical decisions, and the exhaustion of fighting your own institution to do your work properly. By making bureaucracy a central antagonist, MAS*H transcended being merely an anti-war show and became a commentary on how systems can fail the people they’re meant to serve. This resonates just as powerfully today in discussions about healthcare, education, and government services.

War Itself: The Ultimate Antagonist

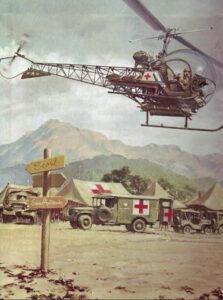

The most profound and perfect antagonist in MASH was never a character but war itself—specifically the absurdity, waste, and moral corruption inherent in armed conflict. Unlike traditional war stories where battle is a backdrop for heroism, MASH portrayed war as a meat grinder that destroyed bodies, minds, and souls indiscriminately.

This antagonist manifested in multiple ways throughout the series. There were the wounded who kept arriving in waves, each one representing a life interrupted, a family worried sick, a young person facing death or disability before they’d truly lived. There was the moral injury of doctors trained to heal being forced to patch people up just well enough to send them back to killing. There was the psychological trauma that accumulated in everyone from Hawkeye’s increasing instability to Radar’s loss of innocence to Father Mulcahy’s crisis of faith.

What made war the perfect antagonist was its implacability. You couldn’t defeat it with clever schemes or good intentions. The 4077th could save individual lives but couldn’t stop the war. This created a unique dramatic tension—the protagonists were winning every battle (saving patients) while losing the war (unable to stop the carnage). Episodes like “Sometimes You Hear the Bullet,” where Hawkeye loses a childhood friend, or “The Interview,” which showed the psychological toll on everyone, made clear that war was an enemy that defeated everyone eventually, even the survivors.

The series finale, “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen,” crystallized this by revealing that Hawkeye had suppressed a traumatic memory so horrible that it fractured his psyche. War wasn’t just an external threat but an internal poison that changed everyone it touched. This antagonist couldn’t be defeated, only survived, and even survival came at a cost that would last a lifetime.

Why These Antagonists Made MAS*H Timeless

The genius of MAS*H’s antagonists was their complexity and variety. Frank Burns provided comic relief while critiquing blind authority. Charles Winchester challenged the protagonists to examine their own biases and rise to higher standards. Military bureaucracy illustrated how institutions fail their stated purposes. And war itself served as the ultimate undefeatable enemy that gave all the other conflicts weight and meaning.

These weren’t villains to be defeated with a clever plan in twenty-two minutes. They were enduring challenges that required constant struggle, moral courage, and acceptance of ambiguity. This approach to antagonism elevated MAS*H beyond typical television and helped establish the template for prestige drama where conflicts are complex, victories are partial, and the best you can do is maintain your humanity in inhumane circumstances.

Modern shows like The Wire, with institutions as antagonists, or Breaking Bad, where the protagonist becomes his own antagonist, owe a debt to what MASH accomplished. By showing that perfect antagonists don’t need to be evil—they just need to be challenging, realistic, and meaningful—MASH changed television storytelling forever.