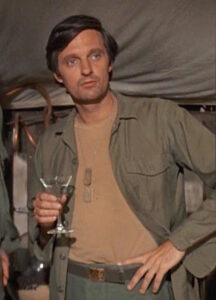

Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce stands as one of television’s most iconic characters—the wisecracking, martini-drinking, authority-defying surgeon whose humor masked profound psychological damage. For eleven seasons, Alan Alda brought Hawkeye to life with such nuance that the character transcended his sitcom origins to become a cultural touchstone representing Vietnam-era disillusionment, anti-war sentiment, and the psychological costs of sustained trauma exposure. But beneath the familiar surface lie fascinating questions about Hawkeye that reveal deeper truths about MAS*H’s themes, creative vision, and revolutionary approach to character development. These three questions unlock understanding of not just Hawkeye but the entire series’ artistic achievement.

Why Did Hawkeye’s Character Change So Dramatically From Early to Late Seasons?

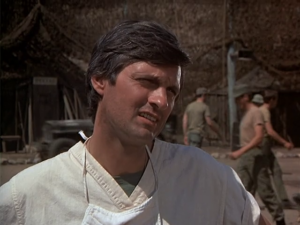

Viewers who watch MAS*H chronologically notice a striking transformation in Hawkeye Pierce’s character. The early-season Hawkeye is lighter, more genuinely playful, and though cynical about war, seems psychologically intact. He pranks Frank Burns, pursues nurses with comic enthusiasm, and maintains emotional distance from the horror surrounding him. By contrast, late-season Hawkeye is visibly damaged—his drinking has progressed from social to concerning, his jokes have desperate edges, and he experiences increasing psychological fragility culminating in complete breakdown in the series finale.

This transformation wasn’t accidental or the result of inconsistent writing. It represented MAS*H’s most ambitious long-term storytelling achievement—a gradual, realistic portrayal of cumulative trauma’s effects on someone experiencing sustained horror without relief. The creative team deliberately showed Hawkeye’s psychological deterioration across 251 episodes, demonstrating that even the most resilient people eventually break under sufficient pressure.

What makes this character evolution fascinating is how it reflected changing understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder during MAS*H’s eleven-year run. When the show premiered in 1972, PTSD wasn’t yet recognized as a diagnosis—that wouldn’t happen until 1980. Early episodes portrayed Hawkeye’s coping mechanisms—humor, drinking, womanizing—as personality quirks rather than trauma responses. As cultural understanding of psychological war wounds evolved, so did the show’s portrayal of Hawkeye’s mental state.

Alan Alda has discussed in interviews how he deliberately played Hawkeye’s deterioration subtly across seasons. He made choices about when Hawkeye’s smile didn’t quite reach his eyes, when jokes landed with harder edges, when drinking transitioned from social to solitary. These gradual shifts created a character arc spanning eleven years that culminated in the finale’s devastating revelation that Hawkeye had witnessed—and felt partially responsible for—a mother smothering her infant to save others from enemy detection.

This character evolution also reflected Alda’s own growing influence over the show’s creative direction. As he became more involved in writing and directing, he pushed for honest exploration of trauma rather than maintaining Hawkeye as a static comic character. The transformation of Hawkeye from lighthearted rebel to psychologically wounded survivor represents television’s evolution from episodic entertainment to sophisticated long-form storytelling where characters bear consequences of their experiences.

Why Was Hawkeye Never Promoted Despite Being the Best Surgeon?

Throughout MAS*H’s eleven seasons, Hawkeye Pierce remained a captain despite being consistently portrayed as the 4077th’s most skilled surgeon and the obvious choice for chief surgeon. Other characters received promotions—Margaret advanced in rank, Winchester arrived as a major—but Hawkeye stayed a captain from the series’ first episode to its last. This wasn’t an oversight; it was a deliberate creative choice that revealed everything about Hawkeye’s character and the show’s anti-authoritarian philosophy.

Hawkeye’s lack of promotion reflected his fundamental rejection of military hierarchy and values. He didn’t want advancement because promotion would mean embracing the system he despised. Accepting higher rank would require conformity to military protocol, would distance him from enlisted personnel he identified with, and would compromise his ability to challenge authority. Hawkeye chose to remain a captain because it allowed him to maintain his outsider status while still practicing medicine.

This choice also demonstrated Hawkeye’s understanding of institutional dynamics. Higher rank would bring administrative responsibilities that would take him away from surgery—the only aspect of military service he valued. Becoming chief surgeon would mean spending time on paperwork, discipline, and bureaucratic nonsense rather than saving lives. Hawkeye recognized that in dysfunctional institutions, advancement often means becoming complicit in the dysfunction you originally opposed.

The show’s decision to keep Hawkeye at captain rank also served narrative purposes. His relatively low rank within the military hierarchy justified his constant conflicts with authority figures and his ability to speak truth to power without facing severe consequences. A major or colonel couldn’t get away with Hawkeye’s insubordination, but a captain—particularly one whose surgical skills made him indispensable—occupied a sweet spot where he could challenge authority while remaining necessary to the institution.

Hawkeye’s static rank also reflected the show’s broader theme about maintaining integrity within corrupt systems. Advancement requires compromise, requires accepting the system’s values and playing by its rules. Hawkeye’s refusal of promotion—whether explicit or simply not pursuing it—represented his determination to remain himself regardless of institutional pressure. He survived eleven years in the Army without letting it change his fundamental values, even as it damaged his psyche.

This choice becomes even more interesting when contrasted with other characters’ relationships to rank. Margaret valued her military status and advancement represented validation of her competence and dedication. Winchester’s rank reflected his aristocratic background and social standing. Potter’s colonel rank came with genuine leadership ability and earned respect. But Hawkeye’s captaincy represented conscious rejection of what rank symbolized—acceptance of military values he fundamentally opposed.

What Does Hawkeye’s Name Reveal About His Character and the Show’s Themes?

Benjamin Franklin Pierce received the nickname “Hawkeye” from his father, who named him after the character Natty Bumppo (known as Hawkeye) from James Fenimore Cooper’s “Leatherstocking Tales,” particularly “The Last of the Mohicans.” This literary reference wasn’t random—it revealed layers of meaning about Hawkeye’s character and MAS*H’s engagement with American mythology and identity.

Cooper’s Hawkeye was a frontiersman who existed between civilizations—too “civilized” to fully belong to Native American culture but too independent and wild to fit into European-American society. He was skilled, self-reliant, and guided by personal ethics rather than institutional rules. This perfectly described MAS*H’s Hawkeye, who existed between military and civilian worlds, never fully belonging to either. He was too skilled and necessary to expel from the Army but too rebellious and anti-authoritarian to ever truly be a military man.

The literary Hawkeye also represented a particular American archetype—the individualist who challenges corruption and fights for justice outside institutional frameworks. He trusted personal judgment over authority, valued competence over credentials, and maintained moral clarity despite surrounding moral ambiguity. These qualities defined MAS*H’s Hawkeye, whose constant challenges to military authority came from genuine moral conviction rather than simple rebelliousness.

The name also connected Hawkeye to American founding values through his first name, Benjamin Franklin. This created interesting tension—Benjamin Franklin represented Enlightenment rationality, civic virtue, and nation-building, while the nickname Hawkeye suggested frontier individualism and rejection of civilization’s constraints. Hawkeye Pierce embodied this tension between civic duty (serving as a doctor saving lives) and individual conscience (refusing to accept military values or war’s legitimacy).

Alan Alda has noted that the name Hawkeye also suggested keen observation—hawks have exceptional vision, seeing details others miss. Hawkeye Pierce saw through military propaganda, bureaucratic justifications, and the various lies people told themselves to make war bearable. His clear-sighted recognition of war’s absurdity and immorality drove both his humor and his psychological damage. He couldn’t unsee what he saw, couldn’t accept comfortable illusions that might have protected his sanity.

The choice to consistently use the nickname rather than his given name also suggested Hawkeye’s rejection of his inherited identity. Benjamin Franklin Pierce was someone’s son, someone from Crabapple Cove, Maine, with a past and family expectations. Hawkeye was who he became in war—a persona built around survival, resistance, and maintaining humanity in dehumanizing circumstances. The name represented self-creation rather than inheritance, which aligned with American mythological emphasis on reinventing oneself.

The Deeper Meaning

These three questions about Hawkeye Pierce—why his character evolved so dramatically, why he never advanced in rank, and what his name reveals—unlock deeper understanding of MAS*H’s artistic achievement. Hawkeye wasn’t just a character but a carefully constructed exploration of trauma, integrity, resistance, and American identity. His gradual psychological deterioration demonstrated television’s potential for sophisticated long-form character development. His static military rank revealed how maintaining personal integrity sometimes requires refusing institutional advancement. His literary name connected him to American mythological traditions while subverting them for anti-war purposes.

Understanding these layers transforms MASH from a well-crafted sitcom into something more profound—a decade-long meditation on what war does to people who maintain their humanity despite sustained exposure to inhumanity, and what it costs to refuse complicity in systems you fundamentally oppose. Hawkeye Pierce remains television’s most complete answer to these questions, and understanding him means understanding why MASH continues resonating with audiences forty years after its conclusion.