With 251 episodes spanning eleven seasons, MASH created an embarrassment of riches for television viewers. The sheer volume of quality content presents a challenge for newcomers and even longtime fans looking to revisit the series’ highlights. Which episodes truly capture the show’s essence? Which represent television at its absolute finest? After decades of critical analysis and fan devotion, certain episodes have emerged as undeniable essentials—the ones that showcase MASH’s unique genius and changed television forever.

These twelve episodes represent the full spectrum of what made MASH extraordinary. They include devastating drama, brilliant comedy, experimental storytelling, character-defining moments, and the kind of profound humanity that transcends entertainment to become genuine art. Whether you’re introducing someone to the series or revisiting it yourself, these episodes constitute the core curriculum of MASH excellence. Together, they tell the story of why this show mattered then and continues resonating now.

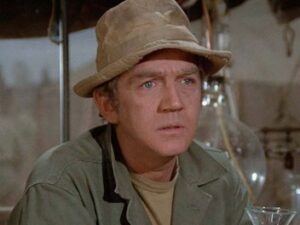

“Sometimes You Hear the Bullet” (Season 1, Episode 17)

This early episode marked the moment MASH transformed from a service comedy into something far more significant. When Hawkeye’s friend Tommy arrives at the 4077th and subsequently dies on the operating table, the show confronted mortality with shocking directness. Alan Alda’s breakdown after losing his friend—his first genuine emotional collapse in the series—established that MASH would explore war’s psychological cost with unflinching honesty.

The episode’s power comes from its refusal to comfort viewers with easy resolutions. Hawkeye can’t save everyone, no matter how skilled or desperate he becomes. Sometimes people die, and the grief is real and lasting. This brutal truth, delivered in the series’ first season, set the template for everything that followed. The episode also features the memorable subplot of Hawkeye treating an underage soldier, forcing him to confront the ethics of sending a child back into combat versus respecting someone’s choice to serve.

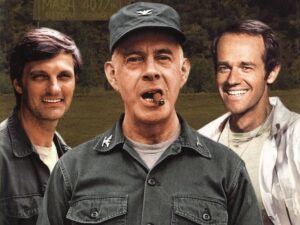

“Abyssinia, Henry” (Season 3, Episode 24)

Television had never done anything quite like this before. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Blake, the camp’s beloved commanding officer, finally receives his discharge orders and heads home to his family. The camp celebrates, everyone says their goodbyes, and Henry boards his helicopter for the journey that begins his trip back to the United States. Then, in the episode’s final moments, Radar enters the operating room and delivers devastating news: Henry’s plane was shot down over the Sea of Japan. There were no survivors.

The shock was deliberate and profound. The cast wasn’t told about Henry’s death until immediately before filming the scene, ensuring their reactions would be genuine. McLean Stevenson’s departure from the show could have been handled conventionally, but the creative team understood that war doesn’t provide happy endings just because someone receives discharge papers. The episode became one of television’s most talked-about moments, proving MAS*H would take risks that other shows wouldn’t dare attempt.

“The Interview” (Season 4, Episode 25)

Shot in black and white with a documentary format, this experimental episode featured a television journalist interviewing the 4077th’s personnel about their experiences. The innovative approach allowed actors to break from their characters’ usual dynamics and speak more directly about war’s realities. The episode contains no laugh track, no conventional plot structure, and no easy answers—just people trying to articulate what living through war actually means.

The brilliance lies in how the format strips away the show’s usual protective layers of comedy and narrative distance. Characters speak to the camera with uncomfortable honesty, revealing fears and doubts they rarely express to each other. The black and white cinematography and documentary style create an almost archival quality, as if we’re watching real historical footage rather than scripted television. It remains one of MAS*H’s most daring and successful experiments.

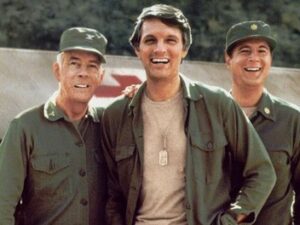

“Welcome to Korea” (Season 4, Episodes 1-2)

This two-part season premiere handled the departures of Trapper John and Frank Burns while introducing BJ Hunnicutt and introducing the circumstances that would lead to Charles Winchester’s arrival. The episodes showcased MAS*H’s remarkable ability to refresh itself, bringing in new characters without losing the show’s essential identity. BJ’s introduction as Hawkeye’s new bunkmate and best friend required delicate handling—he needed to be different from Trapper while still creating believable chemistry with Hawkeye.

The episodes succeed brilliantly, establishing BJ as a more grounded, family-focused counterpoint to Hawkeye’s cynical brilliance. Their first meeting, with both men covered in blood from emergency surgery during a long journey to the 4077th, immediately established their shared experience and mutual respect. The show proved it could survive significant cast changes without losing quality—a rare achievement in television history.

“Dear Sigmund” (Season 5, Episode 8)

This episode featured psychiatrist Dr. Sidney Freedman writing to Sigmund Freud about his experiences at the 4077th. The conceit allowed the show to explore mental health with unusual depth, examining how everyone at the camp coped with constant stress, trauma, and loss. Sidney’s observations about each character revealed psychology lurking beneath surface behaviors, and his own struggles demonstrated that even therapists need support.

The episode’s gentle humor balanced serious examination of post-traumatic stress, alcoholism, and the various defense mechanisms people employ to survive unbearable situations. Sidney’s compassion for everyone—from Hawkeye’s frantic joking to Margaret’s rigid control to Frank’s delusional self-importance—modeled the kind of non-judgmental understanding the show aspired to maintain. It remains one of television’s most thoughtful explorations of wartime mental health.

“Life Time” (Season 8, Episode 11)

This episode unfolds in real time as the surgical team fights to save a critically wounded soldier within the “golden hour” that offers the best chance of survival. The innovation wasn’t just structural gimmickry—the real-time format created unbearable tension as we watched every second tick away while Hawkeye desperately tried procedures he’d never attempted before. The stakes felt visceral in ways conventional editing would have softened.

The episode showcased MAS*H’s mature confidence in its own dramatic capabilities. The surgical scenes contained minimal dialogue, relying on the actors’ faces and the accumulating time pressure to generate suspense. When Hawkeye ultimately saves the soldier through innovative surgery, the relief is immense—but the episode doesn’t let us forget how close they came to failure or that countless other soldiers didn’t receive such fortunate timing or skilled intervention.

“Good-Bye Radar” (Season 8, Episodes 4-5)

Gary Burghoff’s departure as Radar O’Reilly marked the end of an era for MAS*H. These two-part episodes handled his exit with the perfect blend of sentiment and realism that defined the show at its best. Radar leaves not because of trauma or disaster but because his family needs him—his uncle died and his mother can’t manage the farm alone. It’s a perfectly ordinary reason made heartbreaking by our investment in this character and his relationships with everyone at the 4077th.

The scene where Colonel Potter gives Radar his personal horse represents one of television’s most touching father-son moments. Potter’s gruff emotion and Radar’s tearful gratitude capture the deep bonds formed through shared hardship. The episode also features Klinger inheriting Radar’s company clerk position, setting up his character evolution from Section 8 pursuer to surprisingly competent administrator. The transition felt earned rather than forced, honoring both characters in the process.

“Death Takes a Holiday” (Season 9, Episode 5)

Set during Christmas, this episode followed the camp’s desperate attempt to keep a critically wounded soldier alive past midnight so his family wouldn’t forever associate Christmas with his death. The premise could have been maudlin, but MAS*H handled it with typical sophistication, exploring how small acts of compassion matter even in the face of overwhelming tragedy.

The episode balanced this serious storyline with BJ and Hawkeye’s scheme to acquire a much-needed supply of alcohol, and Charles’s surprising generosity toward Korean orphans—a gesture he tries to keep secret, revealing depths his pompous exterior usually concealed. The multiple storylines wove together to explore different expressions of humanity during wartime, demonstrating that goodness persists even in terrible circumstances. The soldier’s death moments after midnight both honors their effort and acknowledges that good intentions can’t always overcome reality.

“Point of View” (Season 7, Episode 11)

This experimental episode shot entirely from the perspective of a wounded soldier created an immersive experience unlike anything else on television. We see only what he sees, hear what he hears, and experience his confusion, fear, and gradual understanding as the 4077th treats his injuries. The innovation required remarkable technical skill and acting discipline—every character had to perform directly to the camera, maintaining the illusion that we’re seeing through the soldier’s eyes.

The result was deeply affecting, placing viewers directly into the experience of being wounded, transported, treated, and eventually recovering. The episode demonstrated MAS*H’s continued willingness to experiment even seven seasons in, refusing to coast on established formulas. It also showcased the ensemble’s talents—with the camera representing a non-speaking character, everyone had to communicate through behavior and dialogue alone, and they succeeded brilliantly.

“Where There’s a Will, There’s a War” (Season 10, Episode 17)

When Hawkeye believes he’s about to die, he distributes his possessions to his friends, with each bequest revealing something about their relationship and his understanding of what each person needs. The episode provided beautiful character moments as Hawkeye explained his choices—giving BJ his motorcycle, Father Mulcahy his bathrobe, Margaret his father’s medical books, and so on. Each gift carried emotional weight and demonstrated how deeply Hawkeye understood everyone around him.

The episode avoided the obvious tragedy of actually killing Hawkeye, instead using the false alarm to explore what people mean to each other and how we express affection through gestures both grand and small. Hawkeye’s relief at surviving was genuine, but the vulnerability he’d shown remained—he’d let people see how much they mattered to him, and those revelations couldn’t be taken back. It was classic MAS*H: using a dramatic premise to explore genuine emotion.

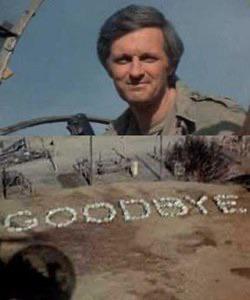

“Goodbye, Farewell and Amen” (Season 11, Episode 16)

The series finale remains the most-watched scripted television episode in American history, with 125 million viewers tuning in to say goodbye to the 4077th. The two-and-a-half-hour conclusion earned its massive audience by delivering everything fans hoped for while refusing to make the ending easy or comfortable. Hawkeye’s traumatic breakdown and recovery, BJ’s desperate attempt to see his family, Margaret’s acceptance of her post-war future, and Colonel Potter’s emotional goodbyes all felt genuine rather than sentimentalized.

The episode’s most controversial and powerful moment—Hawkeye’s revelation that he’d witnessed a mother smother her own baby to prevent its crying from alerting enemy forces—demonstrated MAS*H’s commitment to depicting war’s true psychological cost. The finale could have been purely celebratory, focusing only on the war’s end and everyone going home. Instead, it showed that surviving war doesn’t mean escaping it, and that these experiences would haunt everyone involved for the rest of their lives. It was a perfect, painful, honest conclusion to television’s most ambitious series.

“Tuttle” (Season 1, Episode 15)

This early episode showcased MAS*H’s comedic brilliance. When Hawkeye and Trapper invent a fictitious officer named Captain Tuttle to collect extra supplies and privileges, their elaborate deception spirals into unexpected complexity. The camp begins treating Tuttle as a paragon of virtue—generous, humble, always available to help—forcing Hawkeye and Trapper to maintain an increasingly complicated fiction about this nonexistent person who somehow represents everyone’s ideals.

The episode’s genius lies in its philosophical underpinnings beneath the farce. Tuttle becomes more real through people’s belief in him, raising questions about the nature of existence and whether an idea can be more powerful than actual people. When they finally “kill” Tuttle in a helicopter accident to end the charade, Father Mulcahy delivers a genuinely moving eulogy about a person who never existed. The episode demonstrated MAS*H’s unique ability to be simultaneously hilarious and thought-provoking.

Why These Episodes Define Excellence

These twelve episodes represent MAS*H at its finest—ambitious, emotionally honest, technically innovative, and profoundly human. They showcase the show’s evolution from service comedy to dramedy to something transcending easy categorization. They feature the devastating moments that made viewers cry, the brilliant comedy that made them laugh, the experimental formats that changed what television could be, and the character development that made everyone at the 4077th feel like real people rather than fictional constructs.

Together, these episodes explain why MASH mattered then and continues resonating now. They represent television achieving its full potential as an art form capable of entertainment, enlightenment, innovation, and genuine emotional truth. Whether you watch all twelve in order or sample them individually, they constitute essential viewing for understanding not just MASH but television itself.