When MASH premiered on September 17, 1972, few could have predicted it would become one of the most significant cultural phenomena in American television history. Over eleven seasons, the show evolved from a military comedy into something far more profound—a weekly meditation on war, humanity, friendship, and survival that spoke directly to a nation grappling with Vietnam’s aftermath and searching for meaning in institutional failure. MASH didn’t just entertain; it shaped conversations, challenged assumptions, and demonstrated television’s potential to be art, social commentary, and healing ritual simultaneously. These ten reasons explain why MAS*H became irreplaceable to American television and why its legacy endures decades after its final episode.

It Gave America Permission to Question Authority

MAS*H premiered during the height of anti-Vietnam War sentiment, and though set during the Korean War, everyone understood the show was really about Vietnam. Hawkeye Pierce’s constant challenges to military authority, his questioning of orders, and his insistence that individual conscience outranked institutional demands gave voice to millions of Americans who felt betrayed by government and military leadership. The show argued that blind obedience wasn’t patriotism—it was abdication of moral responsibility.

This anti-authoritarian stance was revolutionary for network television. Previous military shows like “Hogan’s Heroes” or “McHale’s Navy” played authority conflicts for laughs without genuine critique. MAS*H made clear that incompetent or immoral leadership deserved resistance, not obedience. Characters routinely disobeyed orders they considered wrong, and the show portrayed this insubordination as heroic rather than criminal. This message resonated with a generation questioning every institution—military, government, corporate—and validated their skepticism.

The show’s impact extended beyond Vietnam-era viewers. Subsequent generations learned from MAS*H that questioning authority is a civic duty, that individuals bear responsibility for their actions regardless of orders received, and that institutions exist to serve people rather than the reverse. This philosophy influenced how Americans view whistleblowers, protest movements, and institutional accountability.

It Mainstreamed Mental Health Conversations

Decades before PTSD became widely discussed, MAS*H portrayed psychological trauma with unprecedented honesty and sophistication. The show depicted various characters struggling with mental health—Hawkeye’s gradual psychological deterioration, Radar’s anxiety, Margaret’s depression following her divorce—normalizing conversations about psychological wounds that American culture still stigmatized heavily.

The series finale’s revelation of Hawkeye’s repressed trauma and psychiatric hospitalization brought PTSD into millions of homes through a beloved character. Viewers who’d never considered psychological injury as legitimate as physical wounds saw someone they’d known for eleven years completely broken by accumulated trauma. This representation had measurable impact—veteran’s organizations reported increased willingness among Vietnam veterans to seek mental health treatment after the finale aired.

MAS*H argued that psychological damage wasn’t weakness but a natural human response to inhuman circumstances. It showed that the people most damaged by war were often the most sensitive and humane, challenging cultural narratives that equated mental health struggles with character defects. This reframing helped shift American cultural attitudes toward mental health, contributing to gradually reduced stigma and increased treatment-seeking.

It Proved Television Could Be Art

Before MASH, television was considered disposable entertainment—culturally inferior to film or theater. MASH demonstrated that weekly series could achieve artistic sophistication previously reserved for prestige cinema. Its experimental episodes, sophisticated cinematography, complex character development, and willingness to challenge narrative conventions proved television’s artistic potential.

Episodes like “The Interview” (filmed documentary-style in black and white), “Dreams” (featuring surreal dream sequences), and “Point of View” (shot entirely from one character’s perspective) employed avant-garde techniques that expanded television’s creative vocabulary. The show attracted serious critical attention from cultural commentators who’d previously dismissed television as wasteland unworthy of analysis.

This artistic legitimacy changed how creative talent viewed television. Previously, television work was considered a step down from film or theater—something serious artists did only for money. MASH demonstrated that television could be creatively fulfilling and artistically significant, attracting better writers, directors, and actors to the medium. The prestige television era that began with “The Sopranos” and continues today has direct lineage to MASH’s proof that television could be art.

It Created the Modern Dramedy

MASH pioneered the blend of comedy and drama that defines contemporary prestige television. Before MASH, shows were comedies or dramas—genres didn’t mix. MAS*H demonstrated that sophisticated storytelling could shift seamlessly between tones, that humor and tragedy could coexist within single episodes, and that making audiences laugh didn’t preclude making them cry.

This tonal innovation influenced countless subsequent shows. “The Wonder Years,” “Northern Exposure,” “Scrubs,” “The Office,” “Orange Is the New Black,” and dozens of other dramedies exist because MAS*H proved the format’s viability. The show established that mature audiences could handle tonal complexity and that mixing comedy with serious themes often made both more effective.

The dramedy format particularly suited American television’s long-form storytelling potential. Unlike two-hour films that must choose comedy or drama, weekly series could explore both across multiple episodes. MAS*H demonstrated how to use comedy to make drama more accessible and drama to give comedy deeper meaning, creating a template that remains relevant today.

It Made the Personal Political Without Preaching

MAS*H was deeply political—anti-war, anti-authority, skeptical of institutions, critical of military-industrial complex—but rarely felt preachy because it embedded political messages in personal stories. Rather than lecturing about war’s immorality, it showed characters confronting war’s human costs. Instead of abstract arguments about institutional dysfunction, it portrayed specific individuals suffering from bureaucratic incompetence.

This approach made political messages more persuasive because they felt discovered rather than imposed. Viewers reached conclusions through emotional connection to characters rather than being told what to think. When Hawkeye broke down from accumulated trauma, viewers understood war’s psychological costs more powerfully than any statistics or arguments could convey.

The show demonstrated that the personal is political—that individual stories reveal systemic truths. A nurse facing sexual harassment illustrated institutional sexism. A wounded soldier revealing he’s gay demonstrated discrimination’s human costs. These personal stories made abstract political issues concrete and emotionally resonant, changing minds more effectively than direct political argumentation.

It Gave Voice to Vietnam Veterans

Though technically about Korea, MAS*H became the cultural text through which many Americans processed Vietnam. The show aired during and immediately after Vietnam, and its themes—war’s futility, institutional incompetence, psychological damage, moral ambiguity—directly addressed Vietnam veterans’ experiences in ways few other cultural products attempted.

Veterans reported that MASH portrayed war’s reality more accurately than news coverage or political rhetoric. The show’s depiction of black humor as survival mechanism, of medical personnel’s dedication amid chaos, and of psychological costs resonated with people who’d lived these experiences. MASH validated veterans’ memories and emotions when much of American culture wanted to forget Vietnam entirely.

The show also helped non-veterans understand what soldiers experienced, building empathy bridge between civilian and military populations. It humanized service members as complex individuals rather than heroes or villains, helping Americans see veterans as people deserving support rather than judgment.

It Demonstrated Ensemble Storytelling’s Power

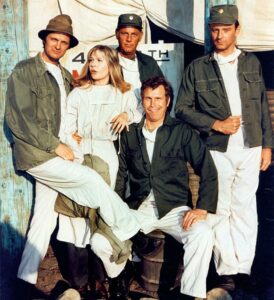

MAS*H featured one of television’s greatest ensembles, demonstrating that shows could thrive by developing multiple complex characters rather than focusing on a single star. Though Alan Alda received top billing, the show gave substantial development to Margaret, Winchester, Potter, BJ, Father Mulcahy, Klinger, and numerous supporting characters.

This ensemble approach allowed for richer storytelling because different characters could carry different themes and perspectives. Episodes could focus on whichever character best suited the story being told. The ensemble also created natural opportunity for examining issues from multiple viewpoints, enriching the show’s exploration of complex topics.

The success of MAS*H’s ensemble influenced subsequent television, from “Hill Street Blues” to “The West Wing” to modern ensemble dramas that recognize multiple developed characters create more storytelling possibilities than single protagonist shows.

It Changed How Series Endings Work

MAS*H’s decision to end on its own terms rather than running until canceled established the planned series finale as television event. “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen” drew 106 million viewers—the most-watched television episode in American history at that time—demonstrating that audiences valued narrative closure and would show up for proper endings.

This established precedent that great shows should end intentionally rather than fading away. Series from “Cheers” to “Friends” to “Breaking Bad” benefited from MAS*H’s demonstration that planned conclusions could provide artistic and emotional satisfaction impossible in shows that simply stop.

The finale’s two-and-a-half-hour length and cinematic scope also elevated what television finales could attempt. It proved that special episodes could justify expanded runtime and production values, treating viewers’ emotional investment with seriousness it deserved.

It Became Shared Cultural Experience

In an era before streaming fragmentation, MAS*H provided weekly shared cultural experience. Monday nights, millions of Americans watched simultaneously and discussed episodes the next day at work, school, and home. The show created common cultural reference points and vocabulary that connected disparate Americans.

This shared viewing created cultural cohesion that’s nearly impossible in today’s fragmented media landscape. MAS*H was appointment television before that term existed—something people scheduled around and prioritized. The series finale became national event, with bars and restaurants broadcasting it, newspapers covering it extensively, and the country essentially pausing to watch together.

This communal aspect made MAS*H more than entertainment—it was ritual, a weekly gathering where America processed war, loss, friendship, and survival together. The show provided framework for collective meaning-making during difficult historical period.

It Proved Television’s Longevity and Evolution

Finally, MAS*H’s eleven-season run demonstrated that television series could maintain quality across extensive runs and that long-form storytelling allowed for character and thematic development impossible in shorter formats. The show evolved dramatically from Season 1 to Season 11, growing more sophisticated and ambitious as it progressed.

This longevity allowed MAS*H to explore characters with depth rarely achieved in entertainment. Viewers literally grew up with these characters, watching them change across years. The accumulation of episodes created rich history that made later episodes more emotionally powerful because of everything that came before.

The show proved that television’s supposedly inferior length compared to film was actually advantage—that serialized storytelling across years could achieve character complexity and thematic depth that two-hour films couldn’t match. This realization helped shift cultural attitude toward television from dismissive to respectful.

The Enduring Legacy

These ten reasons explain why MASH became irreplaceable to American television history and culture. The show didn’t just entertain—it taught America to question authority, talk about mental health, appreciate television as art, and process collective trauma. It pioneered storytelling techniques that define contemporary prestige television and created cultural moments that united the nation. MASH proved television could be significant, meaningful, and lasting rather than disposable and forgettable. Its legacy lives in every dramedy, every planned series finale, every show that dares to make political points through personal stories, and every series that trusts audiences with complexity. MAS*H didn’t just become part of American television history—it fundamentally shaped what American television could be and become.